Recent Federal Circuit Decisions on Obviousness-Type Double Patenting May Shape Life Science Patent Portfolio Management

The Federal Circuit recently decided two appeals, Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC1 (“Ezra”) and Novartis Pharms. Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharm. Inc.2 (“Breckenridge”) that both relate to the effect of obviousness-type double patenting (“ODP”) on pharmaceutical patents that received patent term extension (“PTE”) for FDA regulatory delays per 35 U.S.C. § 156(c). Both cases concern pairs of patents where the primary patent was filed before implementation of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (“URAA”)3 and the reference patent asserted as the basis for ODP was filed after URAA implementation. The Ezra opinion, in particular, may help clarify some issues relating to the effect of ODP on life sciences patenting strategies, but also leaves some important ODP-related issues unresolved. The analysis that follows reviews the state of ODP law following Ezra and Breckenridge and highlights considerations for patent portfolio management when ODP is a concern, particularly for patents that have PTE-extended terms.

Obviousness-Type Double Patenting for Post-URAA Patents

ODP is a judicially created doctrine intended to “prohibit[] a party from obtaining an extension of the right to exclude through claims in a later patent that are not patentably distinct from claims in a commonly owned earlier patent,” often referred to as the “reference patent.”4 Two policy rationales that underlie ODP are “to prevent unjustified timewise extension of the right to exclude granted by a patent,”5 and to protect potential infringers from “harassment by multiple assignees” when the primary and reference patents are owned by different parties.6

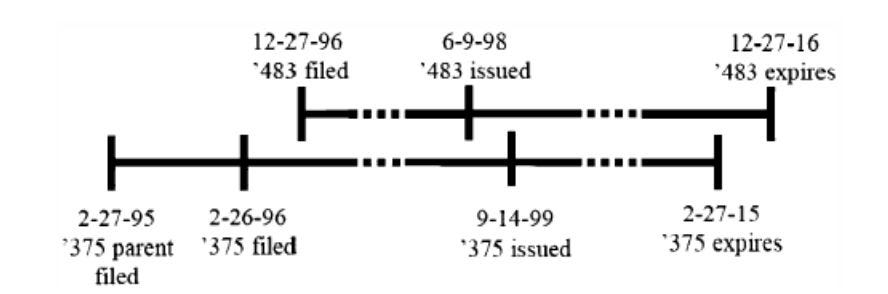

In Gilead Sciences Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., the Federal Circuit held that for post-URAA patents, an earlier-issued, but later-expiring patent, could be invalid for ODP in view of a later-issued, but earlier-expiring reference patent.7 The determination of whether there was an unjustified extension of time was based on which patent had the later expiration date, rather than the sequence in which the patents issued.8 According to the Gilead decision, Gilead’s earlier-issuing ’483 patent issued as a valid patent, but then automatically became invalid for ODP when the earlier-expiring ’375 patent subsequently issued.9

The Gilead majority reasoned that its rule “[p]ermitting any earlier expiring patent to serve as a double patenting reference for a patent subject to the URAA guarantees a stable benchmark that preserves the public’s right to use the invention (and its obvious variants) that are claimed in a patent when that patent expires.”10 Note that the Gilead decision contrasts with pre-URAA ODP analyses, where the issue date determined whether there was ODP, because prior to implementation of the URAA the issue date determined expiration date.11

Concerns over a potential for what it termed “significant gamesmanship during prosecution,” drove the Gilead majority to assign the earlier-expiring patent as the reference patent, regardless of whether it issued first.12 Gilead filed the application that became the ’483 patent in a separate and later-filed family, without claiming priority to the earlier-filed application that became the ’375 patent,13 effectively obtaining a later-expiring term in exchange for potential increased exposure to prior art. The Gilead decision, however, does not address whether two patents in the same family (or having the same effective non-provisional filing date), but with different expiration dates due to Patent Term Adjustment (“PTA”) under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b) or PTE under 35 U.S.C. § 156(c), could be invalid for ODP.

In the post-URAA framework, PTA was enacted to compensate for loss of effective patent term due to USPTO delays during prosecution, derivation proceedings, secrecy orders, and appeals.14 Unlike the situation in Gilead, a patent that receives additional term from PTA does not expire later because of the patentee’s actions, such as securing a later filing date. But a Western Michigan district court nonetheless applied Gilead to a circumstance where the later-expiring patent’s additional term arose from a PTA.15

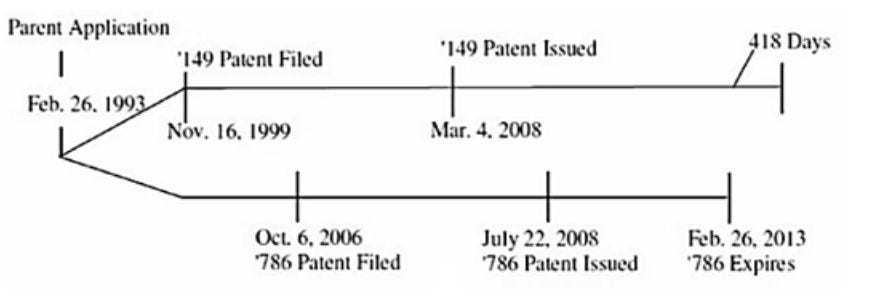

In Magna, the ’149 and ’786 patents share the same parent application, and thus the same effective filing date, but the earlier-filed and earlier-issued ’149 patent received a PTA of 418 days, so it expired later than the later-filed and later-issued ’786 patent.16 The Magna district court found the ’149 patent invalid for ODP by concluding that the PTA was an “unjustified” extension of term, relying on Gilead for the proposition that “expiration dates, not issuance dates, are determinative in assessing a double patenting defense” in post-URAA patents.17 The district court, however, did not address the fact that the additional term in the ’149 patent was a statutorily prescribed remedy for USPTO delay, and not attributable to any action by the patentee to obtain additional term. Because Magna settled without appeal, the issue of whether ODP can nullify term extensions conferred by a PTA remains unsettled.

Ezra Holds that PTE Alone is Not an Unjustified Extension in Term

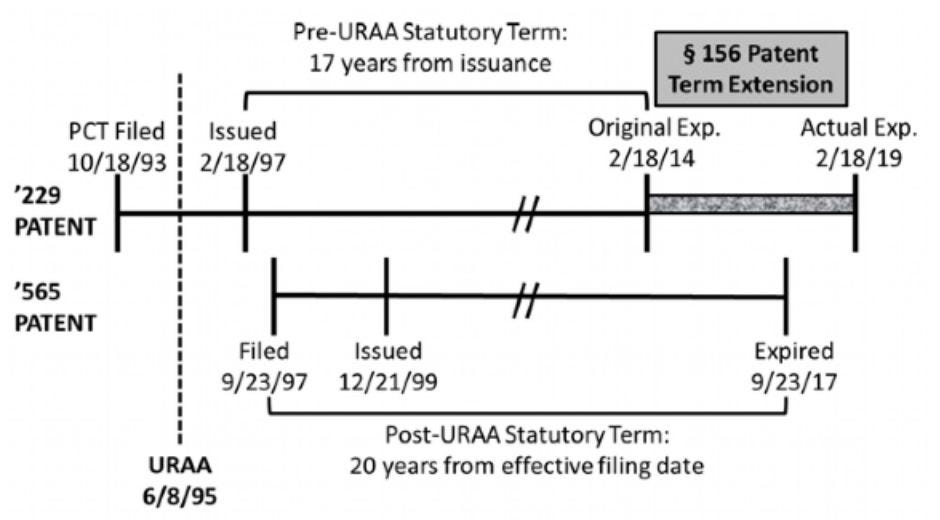

Ezra addresses the question of whether PTE alone can give rise to an “unjustified” extension in term that can provide the basis for ODP. In Ezra, the ’229 patent (directed to compounds) was originally set to expire in February 2014, before the September 2017 expiration of the later-issued ’565 patent (directed to methods of treating), but the ’229 patent received PTE to extend its term to February 2019, past the expiration of the ’565 patent.18 Terminal disclaimers were not filed in either the ’229 or ’565 patent.

Ezra argued that PTE, which extended the term of the ’229 compound patent beyond the ’565 patent’s expiration “is impermissible because it: (1) de facto extends the life of the method patent, and thereby violates the provision of 35 U.S.C. § 156 requiring that ‘in no event [may] more than one patent be extended ... for the same regulatory review period for any product;’ (2) violates the ‘bedrock principle’ that the public may practice an expired patent; and (3) renders the ’229 patent invalid for statutory and obviousness-type double patenting."19

The Federal Circuit, however, rejected Ezra’s arguments and held that the extension of the term of the ’229 patent past that of the ’565 patent by PTE is permissible under 35 U.S.C. § 156, relying on the Federal Circuit’s Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co. holding.20 In Merck v. Hi-Tech, the Federal Circuit held that a terminally disclaimed patent — the terminal disclaimer was filed to overcome ODP over a reference patent — could still receive the benefit of PTE added to the terminal disclaimer-adjusted expiration date, thereby extending the term of the terminally disclaimed patent beyond the term of the reference patent.21

Ezra effectively extends Merck to cover a situation where no terminal disclaimer was filed prior to the expiration of the reference patent provided that the “patent, under its pre-PTE expiration date, is valid under all other provisions of law.”22 The Ezra decision does point out, however, that PTE cannot immunize a patent from ODP, stating that “if a patent, under its original expiration date without a PTE, should have been (but was not) terminally disclaimed because of obviousness-type double patenting, then this court’s obviousness-type double patenting case law would apply, and the patent could be invalidated.”23 Acknowledging that PTE is a statutory extension of patent term, and ODP is a judicially created doctrine, the Federal Circuit in Ezra declined to apply “judge-made doctrine [to] cut off a statutorily-authorized time extension” from PTE.24 Although Ezra arose from a PTE-extended pre-URAA patent, the opinion indicates that a post-URAA patent with added term solely attributable to PTE would not be held invalid for ODP over a reference patent having an original expiration that was the same as, or later, than the PTE-extended patent’s original expiration.

Breckinridge Holds that Additional Term from Pre-URAA Statutes Is Not an Unjustified Extension of Term

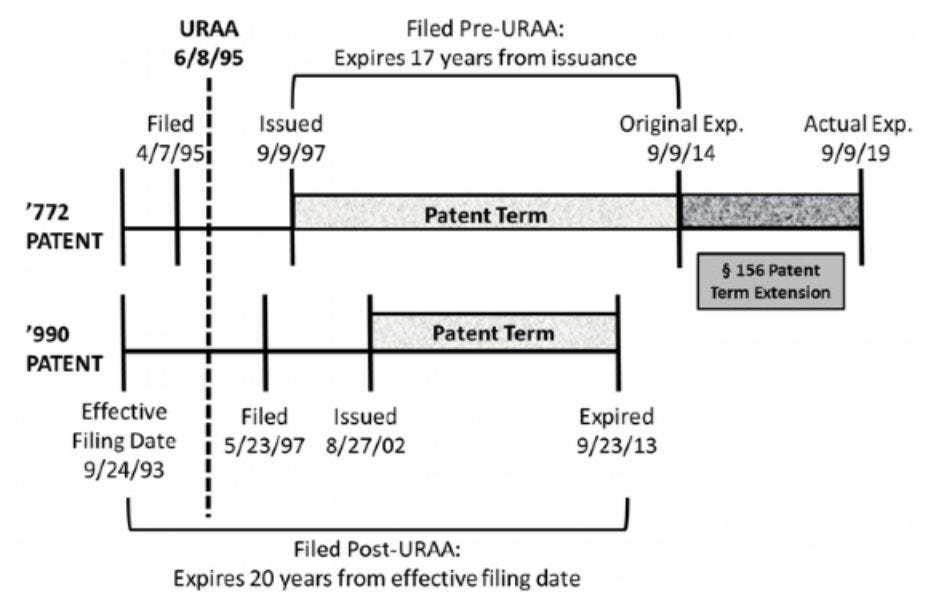

In contrast to Ezra, Breckenridge concerns a situation where the PTE-extended patent had an original expiration date that was later than that of the reference patent.25 The Federal Circuit held in Breckenridge that the PTE-extended patent was not invalid for ODP, however, because it was filed under the pre-URAA law and its later original expiration date was attributable to the way expiration dates were determined under pre-URAA law.26

The ’772 patent was filed under pre-URAA law, so it was slated to expire 17 years after its date of issue, whereas the ’990 patent was filed under post-URAA law, so it was slated to expire 20 years after its effective non-provisional filing date. To its original term, the ’772 patent also benefited from five additional years of PTE.27

Relying on Gilead, the district court found that the post-URAA ’990 patent is a proper ODP reference against the pre-URAA ’772 patent, and held the ’772 patent claims invalid as not being patentably distinct over the claims of the ’990 patent.28 The Federal Circuit, however, reversed the district court by holding that it was improper to apply Gilead to the pre-URAA ’772 patent, because Gilead applied only to circumstances where the later-expiring patent is governed by post-URAA law, which was not the case in Breckenridge.29 Under pre-URAA ODP law, “courts looked at the issuance dates of the respective patents, because, under the law pre-URAA, the expiration date of the patent was inextricably intertwined with the issuance date, and used the earlier-issued patent to limit the patent term(s) of the later issued patent(s).”30 Thus, “regardless of whether Novartis obtained the ’990 patent, the ’772 patent would have expired on September 9, 2014 (September 9, 2019 with the patent term extension)” and by filing the ’990 patent after the change in law, Novartis was likely deprived term in the ’990 patent.31

ODP Issues to Consider in Managing a Patent Portfolio

Ezra and Breckenridge clarified that if a patent remains valid within its original term, without PTE extension, then that patent will remain valid during its PTE-extended term. Ezra also clarified that PTE cannot rescue a patent that is already invalid for ODP.32 This means that a PTE-extended patent can be invalidated for ODP if its original expiration, before adding a PTE, is unjustifiably later than that of the reference patent.

In many instances, ODP can be overcome by filing of a terminal disclaimer, which causes the term of the later-expiring patent to be truncated and expire when the earlier-expiring reference patent expires. Preconditions to a terminal disclaimer require that the patents are commonly owned33 and the reference patent is pending when the terminal disclaimer is filed.34 Provided the preconditions to filing a terminal disclaimer are met, a terminal disclaimer can even be filed after a finding of ODP during litigation.35

Of course, shortening of term from filing a terminal disclaimer can be a major disadvantage. But crucially additional term due to PTE is not impacted by a terminal disclaimer,36 and often in the life sciences additional term attributable to a PTE is significantly longer than term lost to a terminal disclaimer. If ODP could present a risk to a PTE-extended patent, the expiration dates of potential reference patents should be carefully monitored to ensure that, if necessary, a terminal disclaimer can be filed before expiration date of potential reference patents. As Ezra suggests, if a post-URAA PTE-extended patent’s original expiration is later than a reference patent’s expiration, a court finds ODP, and a terminal disclaimer is not filed to cure ODP prior to expiration of the reference patent, then additional term from the PTE may be “lost” when the PTE-extended patent is invalidated for ODP.

The scenario that neither Ezra nor Breckenridge addressed is whether an earlier-issued patent, with a later expiration due to PTA could be invalid over a related reference patent that has the same original expiration date, but no added term. While the Magna district court decision, relying on Gilead, found that additional term from PTA could render a patent invalid for ODP, the Ezra opinion suggests that an earlier-issued patent extended by PTA may not be unjustifiably extended, and thus not invalid under ODP. In reference to PTE, the Ezra panel states that “this court has described obviousness-type double patenting as a ‘judge-made doctrine’ that is intended to prevent extension of a patent beyond a ‘statutory time limit.’... Here, agreeing with Ezra would mean that a judge-made doctrine would cut off a statutorily-authorized time extension.”37 Like PTE, PTA is a statutorily provided extension of a patent’s term under 35 U.S.C. § 154(c), which is not a product of a patentee’s actions, but rather USPTO delays.

Although, this statement in Ezra suggests that later expiration due solely to PTA may be immune from ODP (as with PTE), because this question has not explicitly been taken up by the Federal Circuit, it remains unanswered. Unlike PTE, which is immune to terminal disclaimer, PTA can be disclaimed.38 In the life sciences — where PTE is often added on top of PTA to extend the term of a patent for many years — patent practitioners and portfolio managers must continue to weigh the risk of having a PTA-extended patent invalidated for ODP against the loss of PTA term from filing a terminal disclaimer in order to safeguard term added by a PTE.

Footnotes

1) Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC, No. 2017-2284 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 7, 2018) (“Ezra”).

2) Novartis Pharms. Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharm. Inc., No. 2017-2173 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 7, 2018) (“Breckenridge”).

3) Since June, 8 1995, U.S. patents have had a patent term of twenty years measured from the earliest effective non-provisional filing date to which a patent can claim priority. See 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2). “The term of a patent that is in force on or that results from an application filed before [June 8, 1995] shall be the greater of the 20-year term as provided in subsection (a), or 17 years from grant, subject to any terminal disclaimers.” 35 U.S.C. § 154(c)(1).

4) Eli Lilly & Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 251 F.3d 955, 967 (Fed. Cir. 2001); see also, e.g., In re Longi, 759 F.2d 887, 892 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (ODP “prohibit[s] the issuance of the claims in a second patent not patentably distinct from the claims of [a] first patent.”).

5) In re Schneller, 397 F.2d 350, 354 (CCPA 1968).

6) In re Griswold, 365 F.2d 834, 840 n.5 (CCPA 1966); In re Fallaux, 564 F.3d 1313, 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

7) Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208, 1217 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

8) Id.

9) Id. at 1215-16.

10) Id. at 1216.

11) Id. at 1211.

12) Id. at 1215.

13) Id. at 1215-16.

14) See 35 U.S.C. § 154(b).

15) Magna Elecs., Inc. v. TRW Auto. Holdings Corp., No. 12-cv-00654, 2015 WL 11430786, *3, 4-5 (W.D. Mich. Dec. 10, 2015).

16) Id. at *3.

17) Id. at *4.

18) Ezra, No. 2017-2284, slip op. at 4.

19) Id. at 4-5.

20) Id. at 10-11 (citing Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co., 82 F.3d 1317, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2007)).

21) Merck, 82 F.3d at 1323.

22) Note that the ’229 patent had entered the PTE portion of its term and the ’565 patent had expired, so it was no longer possible to cure ODP in the ’229 patent by filing a TD therein over the ‘565 patent. It seems that a TD in the ‘229 patent would not have impacted its term, either before PTE was applied (because the ‘229 patent expired sooner) or after PTE was applied (in view of Merck v. Hi-Tech).

23) Id. at 12.

24) Id. at 13.

25) Breckenridge, No. 2017-2173, slip op. at 13.

26) Id. at 19-20.

27) Id. at 7.

28) Novartis Pharms. Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharmaceutical Inc., 248 F.Supp.3d 578, 588 (D. Del. April 3, 2017).

29) Breckenridge, No. 2017-2173, slip op. at 19-20.

30) Id. at 11.

31) Id. at 19-20.

32) Ezra, No. 2017-2284, slip op. at 12.

33) See In re Hubbell, 709 F.3d 1140, 1149 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (Holding that a terminal disclaimer cannot resolve ODP where the patent and reference patent are not commonly owned).

34) Boehringer Ingelheim Intern. GmbH v. Barr Labs., Inc., 592 F.3d 1340, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (Holding “that a terminal disclaimer filed after the expiration of the earlier patent over which claims have been found obvious cannot cure [ODP].”).

35) Id. at 1347.

36) Merck, 82 F.3d at 1323.

37) Ezra, No. 2017-2284, slip op. at 13.

38) 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(B) (“No patent the term of which has been disclaimed beyond a specified date may be adjusted under this section beyond the expiration date specified in the disclaimer.”).