Federal Circuit Tailors its Decision on Skinny Labels

As we sensed when we last wrote about the Federal Circuit’s handling of the infringement dispute over GlaxoSmithKline’s ("GSK") Coreg® product in GlaxoSmithKline LLC, v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., the Judges have dug into their original opinions of the case. The majority (Chief Judge Kimberly A. Moore and Judge Pauline Newman) once again vacated the U.S. District of Delaware Judge Leonard P. Stark’s grant of Judgment as a Matter of Law ("JMOL") and reinstated a jury verdict of induced infringement by Teva. However, this time, the majority attempted to allay the concerns expressed by amici by tailoring it to the specific facts of the case. Once again, Judge Sharon Prost, issued a vigorous dissent, stating that “our law on this issue has gone awry,” and that the “new opinion does little to assuage, and even exacerbates, concerns raised by the original.”1

Factual Background

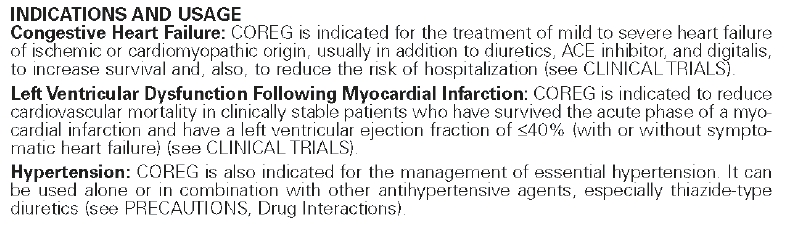

This case involves Teva’s abbreviated new drug application (“ANDA”) for a generic version of GSK’s Coreg® (carvedilol) product, commonly known as a “beta blocker.” Coreg® is indicated for the treatment of hypertension, for left ventricular dysfunction following myocardial infarction (“post-MI LVD”), and congestive heart failure. At the time of Teva’s ANDA submission, GSK had three patents listed in the Orange Book for its product: (1) the ’067 patent for carvedilol, (2) the ’069 patent for a method of treatment for decreasing mortality resulting from congestive heart failure, and (3) the ’821 patent also related to a method for treating congestive heart failure.

Teva filed its ANDA for carvedilol in 2002. Teva certified under Paragraph III of the Hatch Waxman Act that it would not launch its product before the carvedilol ’067 patent expired in 2007. Teva certified under Paragraph IV of the Hatch-Waxman Act that the ’069 and ’821 patents were invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed. GSK did not sue Teva for infringement of the ’821 or ’069 patents and instead sought reissue of the ’069 patent, which issued as the ’000 patent on January 8, 2008, and expired June 7, 2015. Teva launched its generic carvedilol product in 2007 when GSK's ’067 patent expired. When Teva launched its generic product in 2007, it utilized a provision of the Hatch-Waxman Act to “carve out” from its label the use of its product for treatment of congestive heart failure, in an attempt to avoid liability for infringing the ’069/’000 patent—a practice commonly referred to as “skinny labeling.”2 Here, Teva’s label carved out congestive heart failure until 2011, when the FDA required Teva to amend its label to be identical to GSK’s label for Coreg®. GSK sued Teva in 2014 for inducing infringement of the ’000 patent.

Procedural Background

Our prior article provides a more detailed account of the procedural history of this case. Accordingly, we provide a brief reminder of the key events in the case here.

The Trial

At trial, Teva argued that it could not be liable for induced infringement at all, or at least until 2011 when the FDA required Teva to amend its label to include congestive heart failure. GSK argued that Teva induced infringement of the ’000 patent both before and after the 2011 label change, by leaving in the post-MI LVD indication, therefore not completely carving out treatment for congestive heart failure, and by representing its generic as an exact equivalent to Coreg® in marketing materials including a 2004 and 2007 press release from Teva. The jury concluded that Teva induced infringement over the life of the ’000 patent and awarded GSK US$234 million in lost profits plus US$1.4 million in royalties on the Teva sales.

Judge Stark then granted Teva’s motion for JMOL, finding that the verdict was not supported by substantial evidence because GSK had failed to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that Teva’s alleged inducement caused physicians to prescribe generic carvedilol to treat congestive heart failure, as opposed to other factors such as GSK’s labeling and marketing and the existing knowledge of cardiologists in the field. Judge Stark’s grant of JMOL eliminated the jury’s damages awarded for infringement during both the partial and full label periods.

The Original Federal Circuit Opinion

The Federal Circuit vacated Judge Stark’s grant of JMOL in a split decision. The majority concluded that the District Court applied an incorrect legal standard because “precedent makes clear that when the provider of an identical product knows of and markets the same product for intended direct infringing activity, the criteria of induced infringement are met.”3 The majority, noting the high standard for overturning a jury verdict, found substantial evidence supporting the verdict in the evidence of promotional materials, press releases, product catalogs, and FDA labels that GSK presented to the jury.4

Judge Prost issued a vigorous dissent that “the District Court got it right,” and that the majority holding “is no small matter: it nullifies Congress’s statutory provision for skinny labels—creating liability for inducement where there should be none.”5

Teva moved for en banc rehearing, arguing that the decision spelled the end of skinny labeling provided by Congress in the Hatch-Waxman Act. Amicus briefs poured in fearing that the panel decision, read broadly, could create induced infringement liability for a generic drug manufacturer that uses a skinny label to carve-out a patented indication, but accurately describes its AB-rated6 product as therapeutically equivalent to the branded drug. The Federal Circuit granted Teva’s petition, vacating its judgment and withdrawing its opinion. The Federal Circuit ordered a panel rehearing which was argued on February 23, 2021.7

The August 2021 Federal Circuit Decision

The majority explained that the amici played a key role in vacating its prior decision. In particular, the majority acknowledged the concern shared by Teva and many of the amici that the decision was unclear and upset the balance struck by the Hatch-Waxman Act in permitting skinny labels. The panel agreed with the amici that a generic could not be liable for marketing its product under a skinny label that omits all patented indications, and merely notes—without mentioning any infringing uses—that the FDA had rated its product as therapeutically equivalent to a branded drug. With this clarification the panel set out to explain “how the facts of this case place it clearly outside the boundaries of the concerns expressed by amici.”8

Teva Failed to Adequately Carve Out the Use of Carvedilol Claimed in the ’000 Patent

The majority explained that substantial evidence supported the jury’s finding that the patented use was on the label during both the partial and full label period via the post-MI LVD indication. In other words, Teva failed to effectively carve out all patented indications. Therefore, Teva’s statement that its product was therapeutically equivalent to Coreg® was not a mere notation without mentioning any infringing uses as the amici feared.9

For the partial label period, the panel reasoned that the jury had substantial evidence to support its verdict. This included GSK’s expert going through each element of the claim against Teva’s partial label, and explaining how the post-MI LVD indication encouraged infringement. The majority further addressed Teva and the dissent’s critique that this testimony was at best “describing an infringing use” instead of “encouraging an infringing use” as a proper factual question that the jury resolved in GSK’s favor.

The majority further explained that the label, along with other record evidence such as Teva’s marketing materials and company witness testimony further provided a basis for the jury to find Teva’s intent to induce infringement of the patented method. These included a 2004 press-release (prior to the ’000 patent’s issuance and prior to Teva’s carve-out) that Teva received tentative approval of its product which is an “AB rated generic equivalent of GSK’s Coreg® Tablets and are indicated for treatment of heart failure and hypertension.”10 The majority noted that this press release was evidence of intent to encourage infringement because the reference to “heart failure” did not parse congestive heart failure from heart failure associated with post-MI LVD. Similarly the majority pointed to a 2007 press-release (after the ’000 patent’s issuance and Teva’s carve-out) that Teva received final approval to market its generic version of GSK’s “cardiovascular agent Coreg®,” without any mention of the carved out indication. The majority explained that this was different than holding that an AB rating in a true carve out would be evidence of inducement, because in this case even the partial label induced infringement.11

With respect to the full label period, the majority similarly found substantial evidence supported the jury’s finding by virtue of the full label itself, GSK’s expert’s testimony that the label contained each limitation of the claim, and Teva’s marketing that instructed doctors to consult the label in prescribing its product.12

Causation

To establish inducement, a patent owner must show that the accused inducer’s actions actually induced the infringing acts of another and knew or should have known that its actions would induce actual infringement.13 In this case, the causation element of induced infringement took on a heightened importance due to the fact that Teva had actually marketed its product (in contrast to most Hatch-Waxman cases where patent infringement is resolved prior to an ANDA’s approval) and led to sharp disagreement between the majority and dissent.

The majority held that “[i]t was fair for the jury to infer that when Teva distributed and marketed a product with labels encouraging an infringing use, it actually induced doctors to infringe” regardless of whether there was any evidence that a doctor actually prescribed Teva’s product because of Teva’s labeling or marketing.14 The Court left open whether a label—by itself—could be enough to establish causation since Teva distributed other materials in addition to the labels that could have convinced the jury that Teva caused infringement of the ’000 patent.15

By contrast, the dissent boiled down the evidence that the majority relied on for the partial label period as the (1) the skinny label itself, (2) the 2007 press release, and (3) the 2004 press release, and disputed that there was evidence that any of these items actually caused infringement.16 With respect to the full label period, the dissent echoed the District Court, in that there was no evidence that doctors changed the prescribing based on anything Teva had done as opposed to continuing to use the drug as they already had learned to from GSK or other sources. As the majority noted, this interpretation would significantly raise the hurdle for proving induced infringement in any Hatch-Waxman case (regardless of skinny labeling), where physicians formed their prescribing practices based on the innovator’s work that the generic seeks to copy:

To be clear, the dissent would overturn a jury verdict, finding Teva’s full label encouraged doctors to prescribe [in] an infringing manner, as not supported by substantial evidence where the label undisputedly encourages an infringing use[] (CHF) and when Teva tells doctors to read its label for prescribing information. To do so would be a major change in our precedent.17

GSK’s Listing of the ’000 Patent and Equitable Estoppel

This case put a spotlight on the mechanics of skinny labeling and raised concerns by the entire panel as to where Teva went wrong in bringing its generic drug to market. As described above, Coreg® was indicated for the following uses:18

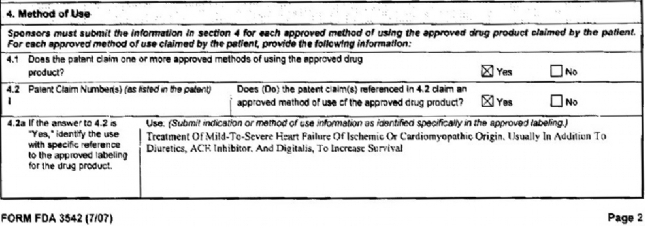

When GSK listed the ’000 patent in the Orange Book, it was required to submit a sworn declaration (Form FDA 3542) describing the use of the drug that is covered in the patent. While this sworn declaration is intended to facilitate the carve-out process, the FDA has stated that it does not analyze patent infringement issues and the use codes are not intended to take the place of the ANDA applicant’s review of listed patents and its proposed generic labeling.19 The form consists of two relevant parts: 4.2(a) and 4.2(b). Section 4.2(a) required GSK to “identify the use with specific reference to the approved labeling for the drug product." GSK filled that section in as “Treatment of Mild-To-Severe Heart Failure of Ischemic or Cardiomyopathic Origin. Usually In Addition To Diuretics, ACE Inhibitor, and Digitalis, To Increase Survival:"20

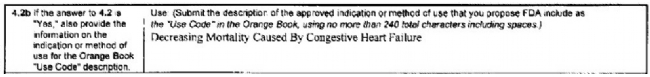

This was almost vertabim to the language used in the Congestive Heart Failure indication for Coreg®. Section 4.2(b), on the other hand, required GSK to provide information on the indication or method of use for the Orange Book “Use Code” description. There, GSK listed the use code as “Decreasing Mortality Caused By Congestive Heart Failure:"21

While there was some question within the panel as to whether section 4.2(a) was available publicly (and thus to Teva), there was no dispute that the FDA and Teva worked together to remove the Congestive Heart Failure indication from Teva’s label, per GSK’s declaration, in order to carve out the use claimed in the ’000 patent.22

The majority viewed GSK’s declaration as relevant evidence that GSK did not consider the post-MI LVD indication as infringing and evidence that Teva—by carving out what GSK said was covered by the ’000 patent in its declaration—had no intent to infringe. While the majority noted that this evidence was “contrary” or “equivocal” to GSK’s other evidence of infringement, the majority found that the jury weighed this evidence and decided against Teva.23 On the other hand, the dissent viewed this evidence as dispositive of Teva’s lack of intent to infringe the ’000 patent during the partial label period.24

The panel also considered Teva’s argument that it relied on GSK’s declaration to carve out the use that GSK said was covered by the ’000 patent and that GSK should be equitably estopped from saying the ’000 patent covers another indication now. However, the Court noted that the issue was preserved at the district court and declined to resolve this issue in the first instance.25 We can expect to see this issue raised on remand.

Key Takeaways

- Brand companies should take care not to short change themselves in preparing the patent-listing declarations submitted to FDA. Here, GSK proved that the post-MI LVD indication would induce infringement, but did not list that indication in section 4.2(a) of its declaration even though it could have. This created the most damaging evidence for GSK and could lead to equitable estoppel on remand.

- Don’t forget causation. While causation can play less of a role in a typical Hatch-Waxman case prior to generic launch, brand companies need to take care to address this element in induced infringement cases. Here, even though there was no direct evidence that Teva’s label or marketing materials actually caused a physician to infringe, GSK provided evidence that Teva encouraged infringement and that physicians would look to those materials.

- This case reinforces that generics cannot rely solely on use codes and the FDA’s suggestions of what to carve out of a label to avoid infringement. Generics need to review the patents and do their own assessment of infringement.

- Generics should work closely with their marketing teams in carve out situations and consider aligning press releases and other marketing materials with the generic label, and educating the teams on the risks of promoting beyond the label.

Footnotes

1) Glaxosmithkline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., Case 18-1976, D.I. 187, at 43, 78 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 5, 2021) (hereinafter “Opinion”).

2) 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(2)(A)(viii).

3) GlaxoSmithKline LLC, v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., 976 F.3d 1347, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

4) Id.

5) Id. at 1358.

6) The FDA assigns an “AB” rating for a drug that is considered therapeutically equivalent to another drug. Opinion at 7, fn. 2. In general, per state automatic substitution laws, a therapeutically equivalent drug will be automatically substituted for a branded drug for all indications on the brand drug label regardless of any carved out indications in the generic label.

7) Glaxo, Case 18-1976, D.I. 181 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 9 2021).

8) Opinion at 10.

9) Opinion at 27-28.

10) Opinion at 28.

11) Opinion at 28, fn. 7.

12) Opinion at 33-34.

13) Opinion at 35 (citing DSU Med. Corp. v. JMS Co., 471 F.3d 1293, 1304 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (en banc)).

14) Opinion at 36.

15) Opinion at 37.

16) Opinion at 56-66.

17) Opinion at 34.

18) Opinion at 51.

19) Opinion at 20-21 (citing 68 Fed. Reg. 36,676, 36,683 (June 18, 2003)).

20) Opinion at 51.

21) Glaxo, Case 18-197, D.I. 88 (Joint Appendix at 6896).

22) Opinion at 51-52, 56-57.

23) Opinion at 19-20.

24) Opinion at 59.

25) Opinion at 22-23, 59-60.