DAMITT 2023 Annual Report: Minding the Gap in Merger Enforcement

Key Facts

United States

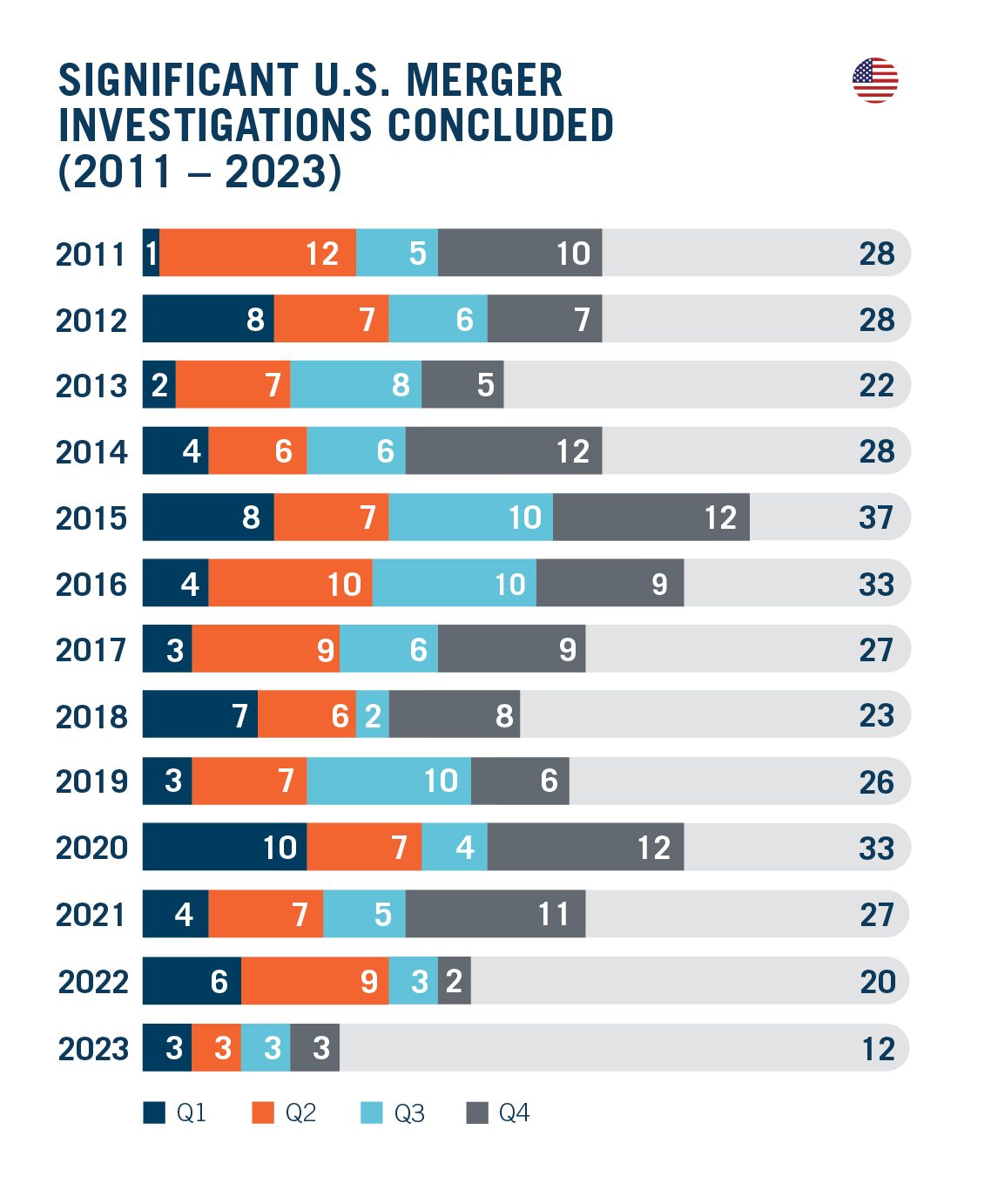

- Only 12 significant merger investigations concluded in 2023—a drop of 40 percent from just last year and by far the lowest in DAMITT history. This observed and verifiable drop sharply contrasts with recent reports that Biden’s enforcers are setting new record highs for merger challenges.

- The U.S. agencies did not enter any pre-complaint settlements involving a divestiture or other traditional merger remedy. This reinforces the perception that the agencies will not accept traditional pre-complaint merger settlements under the current administration.

- The average duration of significant investigations over the last quarter fell to 11.2 months, bringing the annual average to 10.6 months—the lowest since 2018. But keep in mind that all but one of those investigations ended with an abandoned transaction or complaint. Merger investigations still may take longer than expected, especially if parties plan to defend a transaction through potential litigation.

European Union

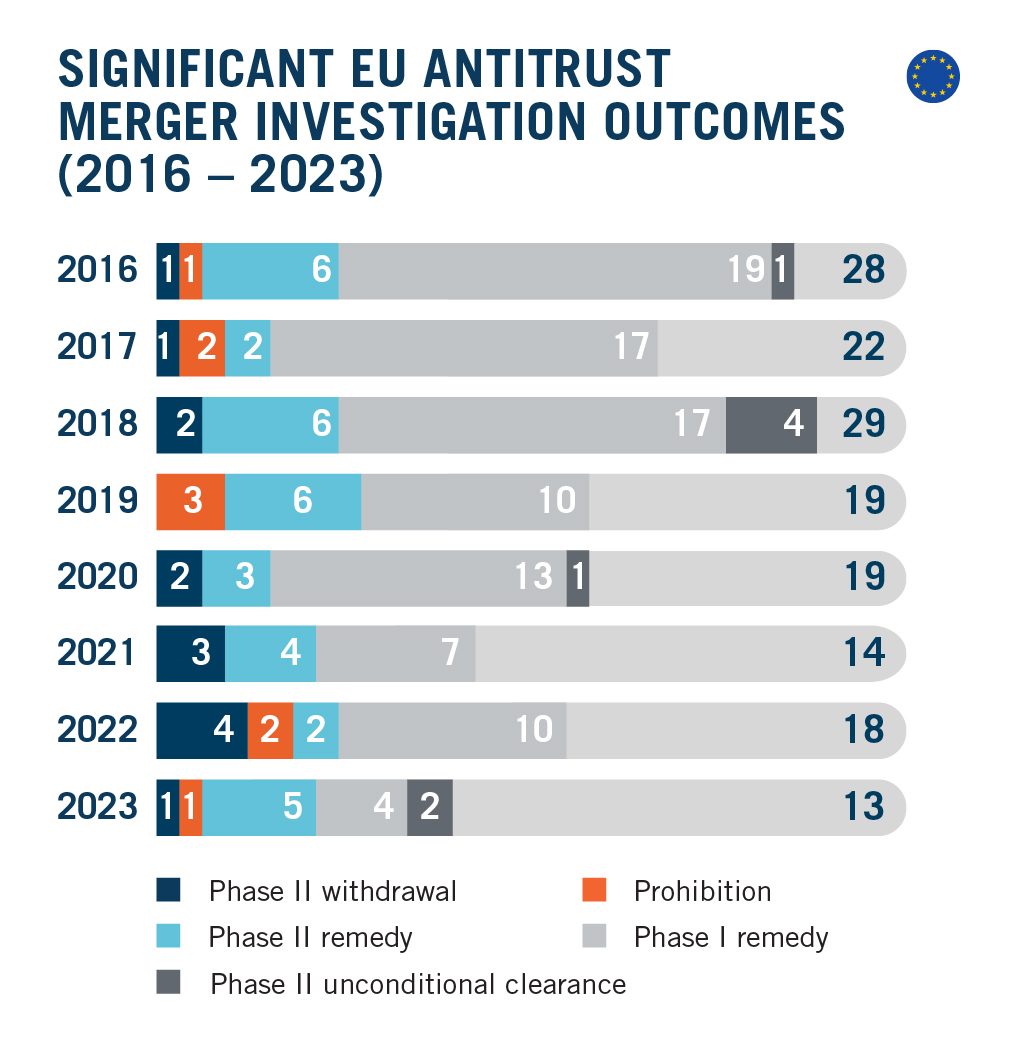

- With only 13 significant merger investigations concluded in 2023, the EC appears to follow the U.S. dip in activity. However, a closer look shows that EU merger enforcement has remained relatively stable since 2019 with significant investigations comprising three percent of notified cases—significantly above the U.S. intervention rate in recent years.

- Phase I Remedy cases are slowly becoming a thing of the past, with a record-low four Phase I remedy cases concluded in 2023 and an increasing proportion of cases being sent to in-depth investigation, driven by the timing constraints of the EU merger regulation and the increasing complexity of the assessments to be carried out.

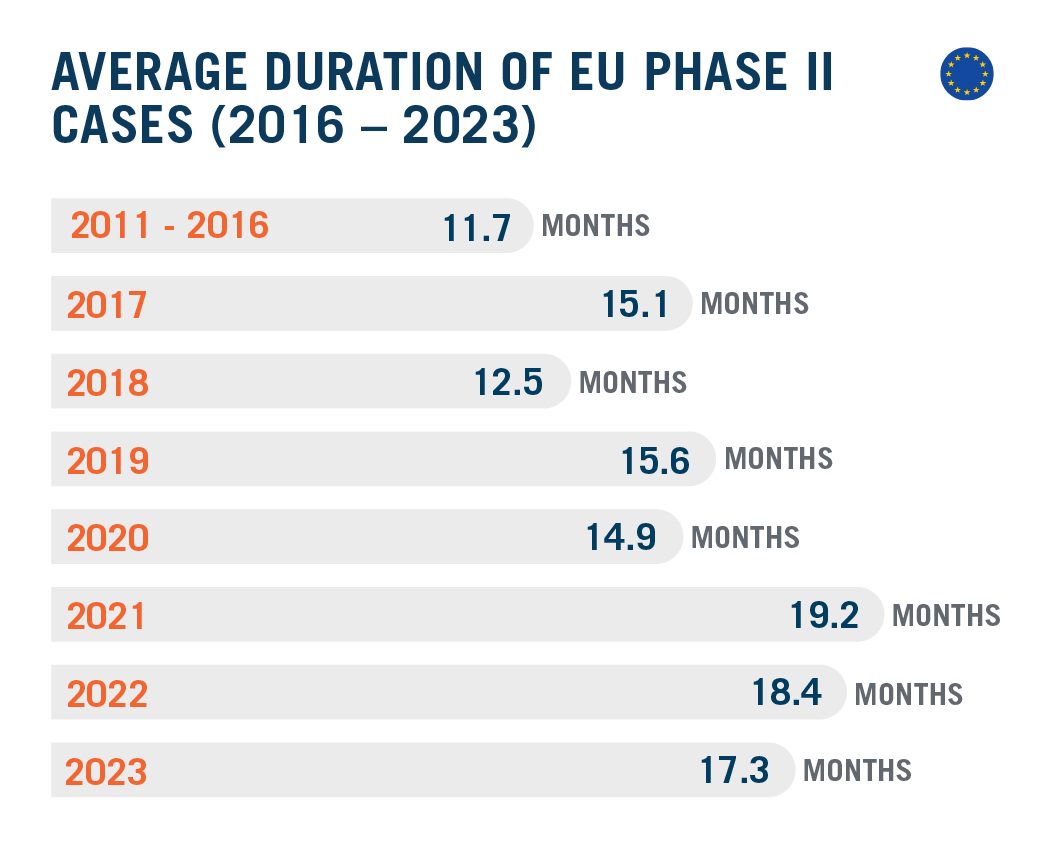

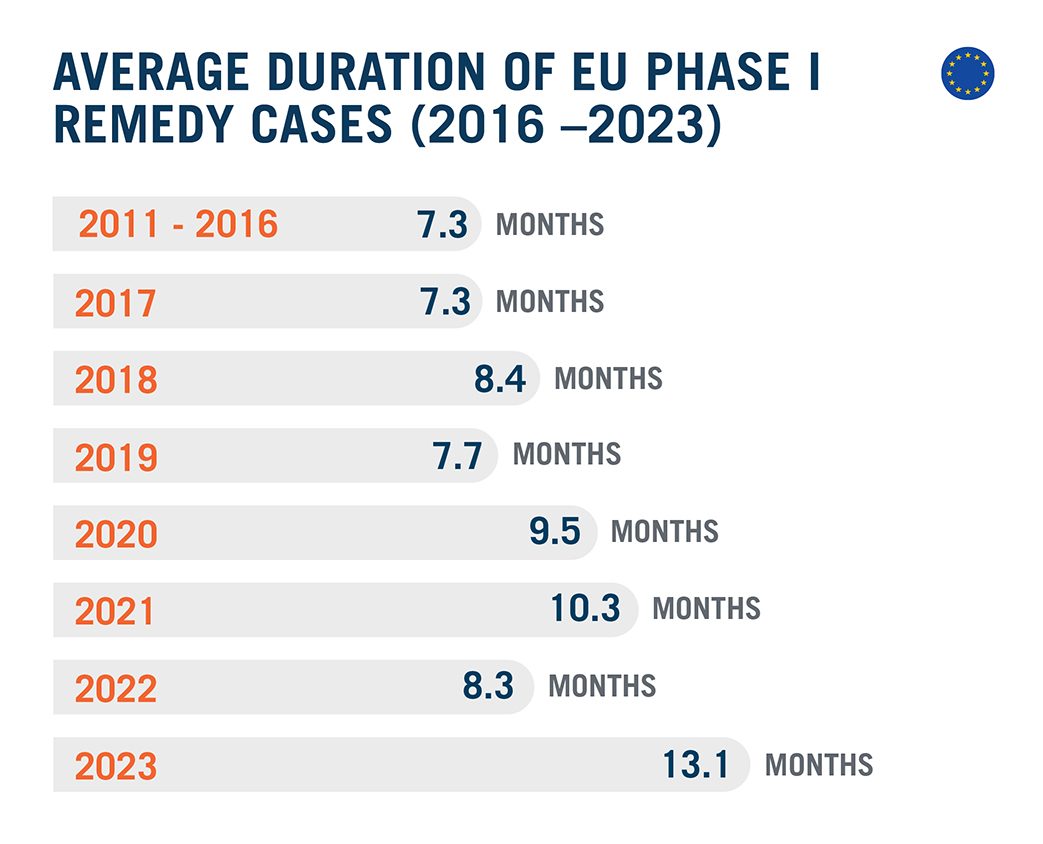

- The average duration of Phase II investigations continued to decrease but remained significant, averaging 17.3 months in 2023. Meanwhile, the average duration of the remaining Phase I remedy cases skyrocketed to 13.1 months, 65.8 percent above 2011-2022 average.

Historically Low U.S. Merger Enforcement Levels and Lower Durations Mask Real Issues that May Torpedo Transactions

Number of Concluded Significant Investigations Hits Historic Low Despite Reports to the Contrary

We at Dechert started DAMITT years ago to address the lack of good data on merger investigations from either agency. In the U.S., our data tracks all investigations that end in a consent order, a complaint challenging a transaction, an official closing statement by the agencies, or the abandonment of a transaction with the agency issuing a press release. We chose those metrics because they are objective and publicly observable, and we have consistently applied those same standards since our first DAMITT report.

By this objective measure, U.S. enforcement levels simply fell through the floor in 2023. The 12 significant merger investigations actions concluded in 2023 are 40 percent lower than the number concluded in 2022 and 64 percent lower than the last year of the Trump administration. We have seen nothing like it in recent memory.

Among the agencies, the DOJ has been particularly quiet. In total, it only filed one complaint and took credit for two abandoned transactions in 2023. Indeed, the DOJ did not show any activity for two consecutive quarters in the middle of the year, only to resurface in late December by taking credit for the abandoned Adobe/Figma transaction.

In fairness to the DOJ, the sole complaint it filed—against the JetBlue/Spirit merger—was successful at trial. That victory gives the DOJ a 100% success rate for complaints filed in 2023—at least pending appeal. By contrast, 75% of complaints filed by the DOJ in 2022 resulted in a government loss or a settlement. By the number of significant investigations alone, however, 2023 was hardly a banner year at either agency.

Imagine our surprise then when we read press reports—based on the agencies’ most recent HSR Annual Report to Congress (the “HSR Report”)—that the U.S. agencies set a “New Record” high for merger challenges. That feels like a verifiable whopper by DAMITT standards.

Indeed, we have been raising red flags about the low number of observed significant transactions from the U.S. agencies for some time now. In our DAMITT Q1 2023 Report, we asked what three quarters of such low activity said about the health of merger enforcement.

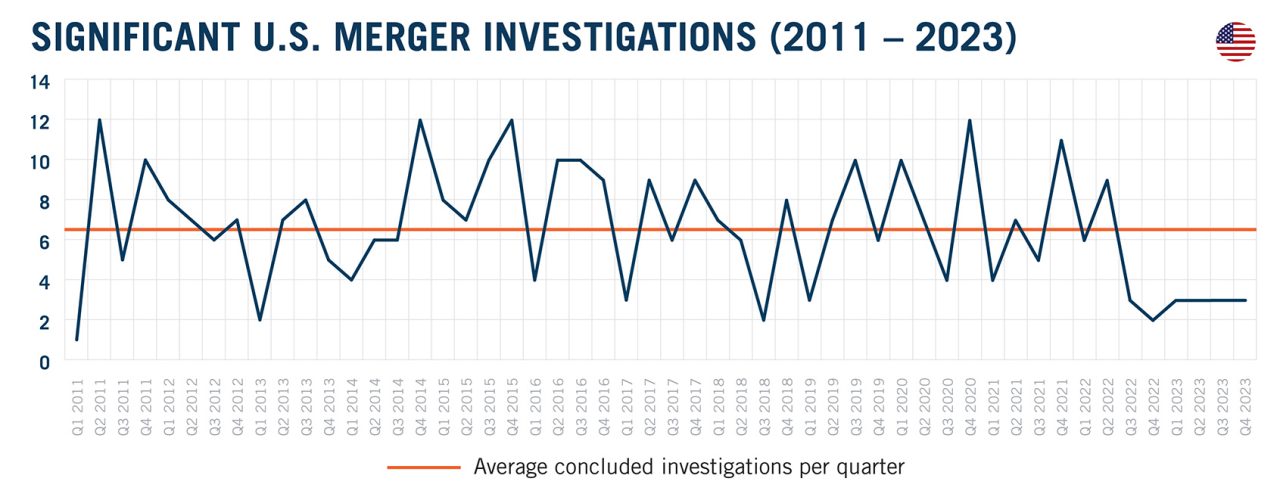

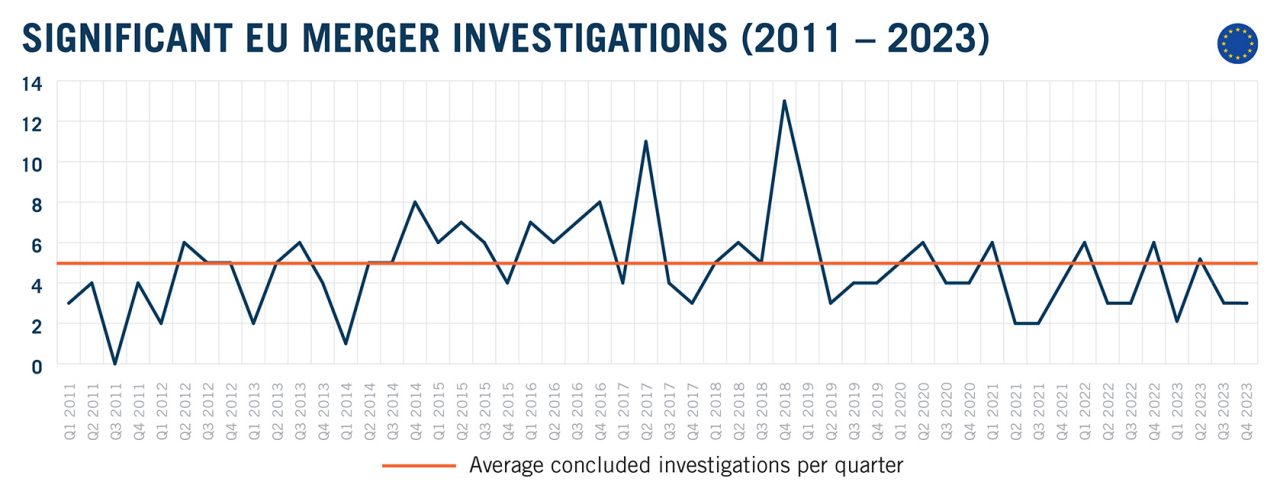

While there typically are quarters with higher and lower levels of concluded investigations, we generally expect to see quarters with higher and lower numbers hover around the average like a heartbeat. But we have now seen six quarters of unusually low activity despite a significant spike in merger filings in 2021 and 2022. A doctor looking at the EKG readout below might well be compelled talk to family members about the patient’s personal affairs.

In our opinion, this is not what a record high looks like. So what explains this apparent gap between the HSR Report released last month and the latest DAMITT data?

We will start with the most obvious: a significant lag in the HSR Report data published by the agencies. Though published in late December 2023, the HSR Report only covers fiscal year 2022, or the period from October 1, 2021, through September 30, 2022. This period only includes the first quarter through which DAMITT has tracked a pronounced drop in merger enforcement. To call this new agency data “stale” would be a bit of an understatement. DAMITT includes a full five more recent quarters at this point. From the perspective of merger enforcement trends, the HSR Report feels like ancient history, especially since it does not report on current merger enforcement operating under the 2023 Merger Guidelines that purportedly “reflect modern market realities.” (We have reported on those developments separately.)

Of course, our annual report last year did not suggest that calendar year 2022 was a banner year for merger enforcement either, and this discrepancy warrants a deeper dive.

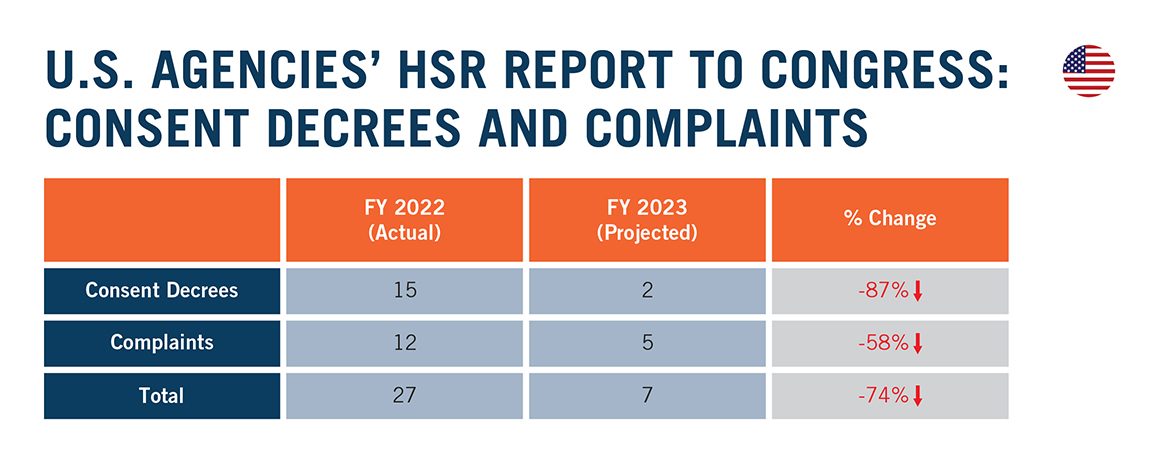

To begin, the HSR Report identifies 15 pre-complaint consent decrees for fiscal year 2022. This is consistent with the DAMITT count over the same period, but that is not surprising, since consent decrees are models of transparency. Among this set of 15, approximately half were filed in 2021, even though three of the four quarters covered by the HSR Report were in 2022. At a high level, that might suggest that the pace of consent decrees was slowing down. At DAMITT, of course, we do not need to just read those tea leaves. Instead, we already know that the pace of pre-complaint consents ground to a halt going into 2023. As a preview for the next HSR Report, the agencies only entered two pre-complaint consent decrees in fiscal year 2023. That is a drop of 87 percent, but you may not get that information from some press sources until the agencies file their next HSR Report to Congress in late 2024. Remember: you heard it here first.

In their HSR Report, the agencies also reported 12 complaints for fiscal year 2022, which again matches our DAMITT data. Yet as a preview for the next HSR Report, the agencies only filed five complaints in fiscal year 2023, amounting to a drop of 58 percent. Looking at pre-complaint consent decrees and complaints together, merger enforcement dropped by 74 percent for the agencies’ fiscal year 2023, as shown below.

What remains is the only area where the figures in the HSR Report do not match the DAMITT data: the agencies’ count of “abandoned or restructured” transactions. DAMITT tracks three abandoned transactions announced by the agencies in fiscal year 2022. By contrast, the agencies’ HSR Report takes credit for 23 “abandoned or restructured” transactions. That is an enormous difference, and the agencies have provided little to no information about those additional transactions to the public at large. This information is not in the DAMITT data precisely because it is not available to the public.

The agencies obviously have more information about non-public transactions, and we rely upon the information they do publish when they make it available. At the same time, there are reasons to question the high counts of abandoned or restructured transactions in the HSR Report.

On November 3, 2023, for example, the FTC Chair sent a letter to Congress with an appendix described as a “comprehensive chart detailing the Commission’s merger enforcement actions from June 2021 to the present”—which includes the full period of the HSR Report. We commend Chair Khan for this level of transparency, but in some ways this chart provides more questions than answers. In particular, the chart lists only two abandoned or restructured transactions for the period covered by the HSR Report. Significantly, the chart includes matter names that were redacted for confidentiality concerns, so it does not appear that any transactions were intentionally omitted for confidentiality reasons. The HSR Report, by contrast, claims that the FTC had seven abandoned or restructured transactions over the same period. In other words, the HSR Report to Congress—published in December 2023—lists 350 percent more FTC merger enforcement actions resulting in an abandoned or restructured transaction for fiscal year 2022 than the number provided in a “comprehensive” chart provided by the FTC Chair to Congress a month earlier. This is the point at which a transparency gap begins to look like a credibility gap.

There also are reasons to question the DOJ count of “abandoned or restructured” transactions in the HSR Report. In past years, for example, the HSR Report consistently identified the number of matters “challenged” by the Antitrust Division. This year, by contrast, the HSR Report identified the number of matters “directly impacted” by the Antitrust Division’s “enforcement efforts.” Similarly, while past reports have referenced transactions abandoned in response to the Division’s “concerns,” the HSR Report this year references transactions abandoned “in the face of questions” from the Division. The change of language here is surprising and notable, and it raises questions about the extent to which this reported surge in abandoned and restructured transactions reflects a genuine trend or the potential widening of the historical criteria for abandoned or restructured transactions to effectively inflate the report’s numbers. It is possible, for example, that these higher counts of “restructured” transactions now include fixes to address Section 8 concerns about interlocking directorates, which traditionally would not have been included within the scope of a merger investigation. We cannot say for sure because the agencies are so opaque with how they compile these figures.

At this point, however, we can confidently report that the numbers in the HSR Report do not add up to the fanfare with which they were announced. In its press release accompanying the HSR Report, for example, the FTC claimed that the agencies together “filed” 50 “merger enforcement actions” in fiscal year 2022. As detailed above, this count of 50 “actions” includes 23 alleged “abandoned or restructured” transactions – seven from the FTC and 16 from the DOJ – that are not the subject of any agency “filing” to date. Merger enforcement filings are distinctly public records. The claim that the agencies “filed” 50 “merger enforcement actions” is not supported by the public record (or even the text of the HSR Report).

Here at DAMITT, we will continue tracking all the information put forward by the agencies to help parties better understand the merger enforcement environment. Parties should understand, for example, that the agencies are taking credit for increasing numbers of abandoned or restructured transactions that may not appear in our data because they are not publicly announced by the agencies. To the extent that is happening, however, we encourage the agencies to publish that information in a more detailed, consistent, and timely manner. Such actions would help dispel some of the broader skepticism about claims of record enforcement that are not otherwise supported by the public record.

From our perspective, the 12 significant merger investigations concluded in 2023 do not look like a record high any way you cut it, and we are confident that the HSR Report eventually published by the agencies for fiscal year 2023 will bear that out.

The Low Number of Concluded Significant Investigations Is Not Just Due to a Drop in HSR Filings

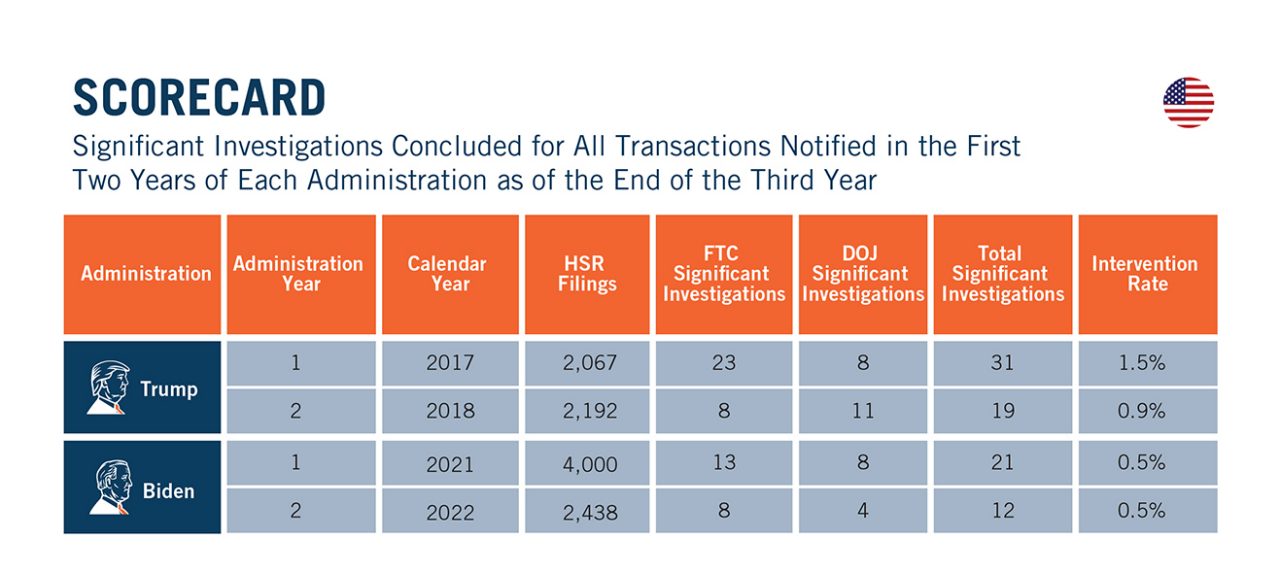

When considering the number of significant investigations, we should also keep in mind the overall number of merger filings. The number of HSR filings dropped in 2022 from a considerable high in 2021, which might lead observers to ask whether the drop in filings is responsible for the drop in significant merger investigations. On that score, however, our data shows that only 0.5 percent of transactions notified in 2022 resulted in a concluded significant investigation, which matches the intervention rate observed for transactions notified in 2021. As shown below, the intervention rate for the first two years of the Biden administration trails the Trump administration at the same point in time. Setting percentages aside, the same is true for the total number of significant investigations over the same period, where the Trump administration is up by 17 significant investigations at the bottom of the second inning. At this rate, it is hard to see the Biden administration catching up any time soon.

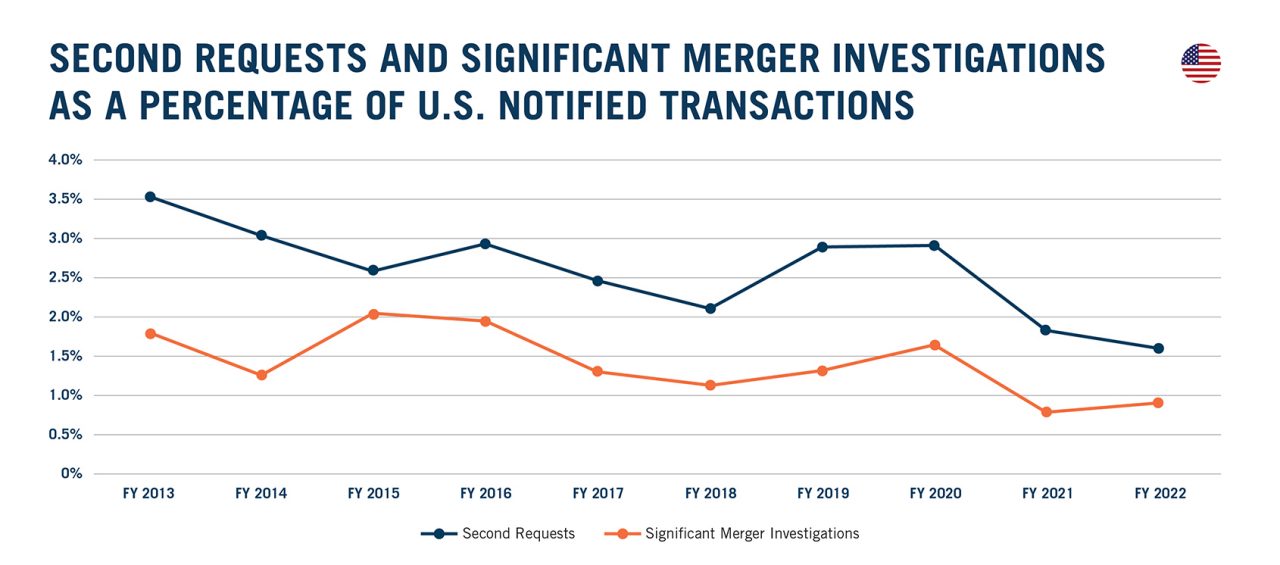

Here it is worth noting that the DAMITT intervention rate is not the same as the number of transactions that received so-called “Second Requests.” DAMITT only tracks significant investigations that were the subject of a consent decree, complaint, closing statement, or agency press release announcing an abandoned transaction. Because investigations under the HSR Act are non-public, DAMITT does not capture investigations that were resolved by the agencies after an investigation without a closing statement. DAMITT also does not capture abandoned or restructured transactions for which the agencies have not issued a press release.

Comparing our data against the agencies’ HSR Report, however, it is apparent that the drop in the percentage of transactions that receive a significant merger investigation matches a parallel drop in the percentage of transactions that received Second Requests.

The low proportion of transactions notified in FY 2022 that received Second Requests helps to explain the low number of significant merger investigations observed in calendar year 2023 given the average duration of significant merger investigations (described in more detail below). It also runs counter to any narrative that FY 2022 was a high-water mark for merger enforcement. Based on the data in the HSR Report, the percentage of transactions issued Second Requests in FY 2022 was the lowest on record since the implementation of the HSR premerger notification program in 1978.

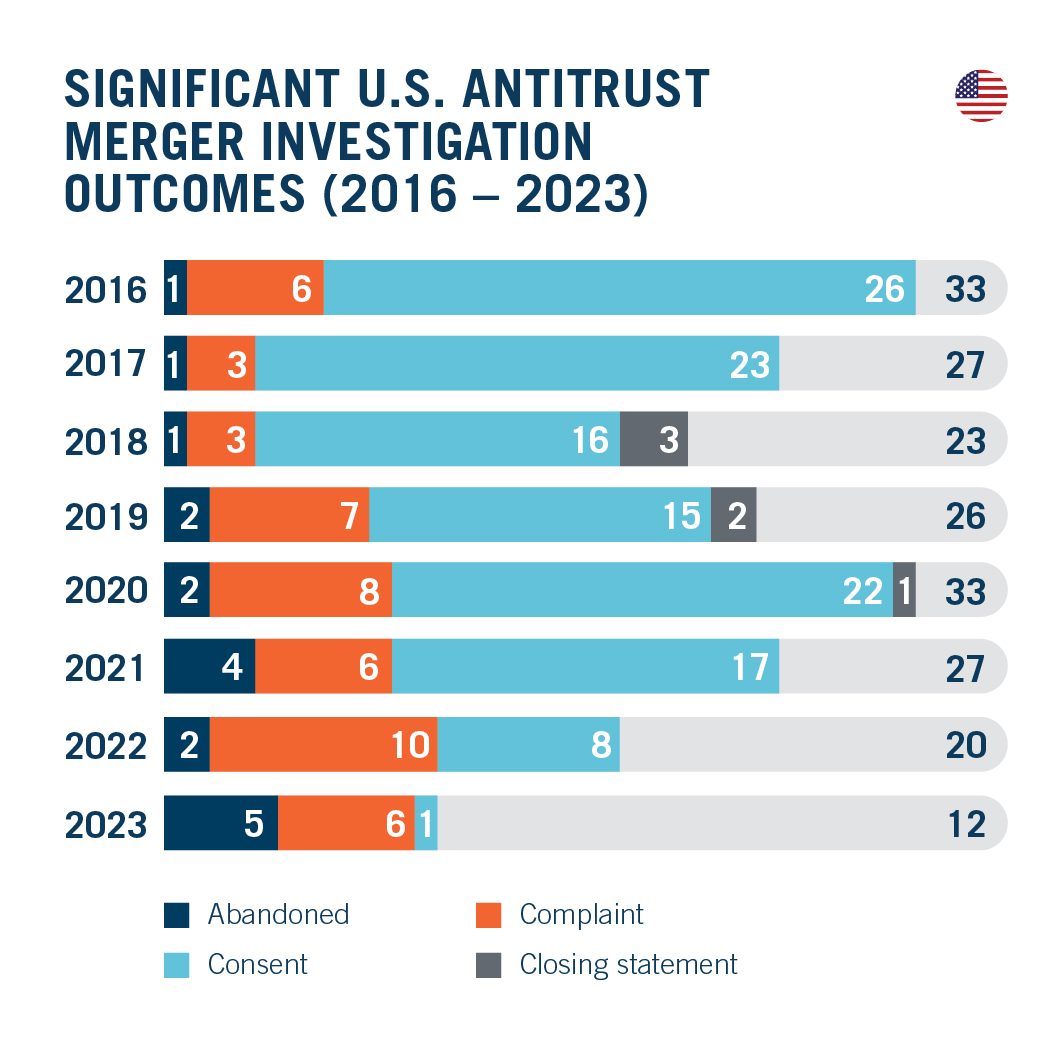

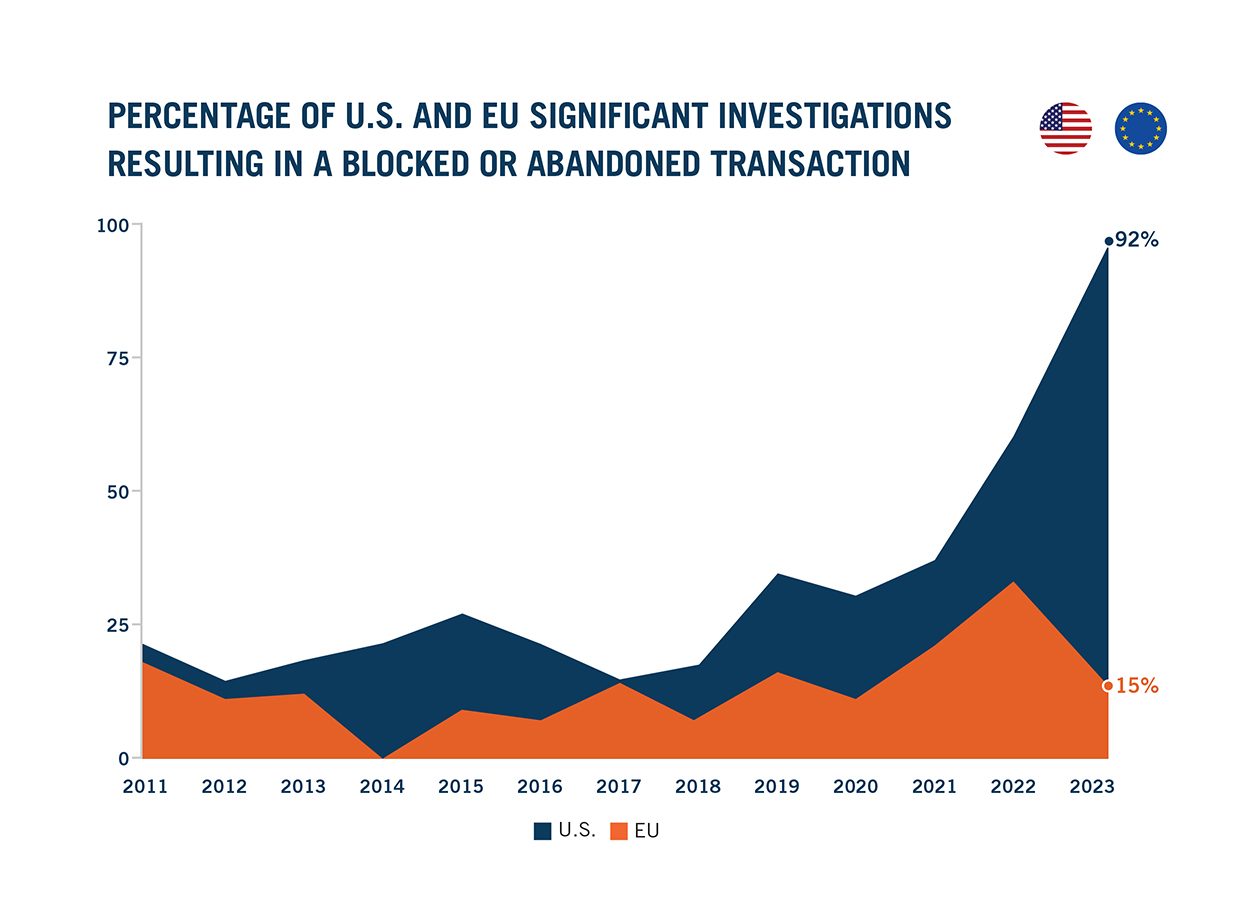

The Agencies Did Not Approve Any Pre-Complaint Settlements with Traditional Merger Remedies

In 2023, the agencies’ war on traditional merger remedies continued unabated. As early as our DAMITT 2021 Report, we have warned that transactions subject to significant merger investigations were more likely to be abandoned or blocked. Back then, 37 percent of significant investigations resulted in a complaint or an abandoned transaction, the highest observed in the DAMITT data going back to 2011. That 2021 record was then shattered in 2022, when 60 percent of significant investigations resulted in either a complaint or an abandoned transaction. And with 2023 over, we can report that the agencies have done it again. In 2023, a full 92 percent of significant merger investigations resulted in either a complaint or an abandoned transaction. Future years should be warned: we are running out of room for new records in this area.

These developments began at the DOJ, which has not entered into a single pre-complaint settlement to resolve a significant investigation since DOJ Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter began warning, shortly after taking office in November 2021, that investigations resolved with merger remedies should be the “exception, not the rule.”

The FTC then followed suit. The former FTC Director of the Bureau of Competition warned in February 2023, “parties should expect the agency to be skeptical and risk averse when considering offers to settle in our merger investigations” before later comparing the FTC’s reluctance to enter into pre-complaint settlements with a prior policy of “getting cookie-cutter consent orders, one after another, on and on and on.”

Keeping true to those words, the only pre-complaint settlement entered by either agency in 2023 was most certainly not a “cookie-cutter” consent order. That order was not intended to remedy any alleged illegal merger under Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Instead, the order was solely directed at resolving an alleged violation of Section 8 related to interlocking directorates. It is, of course, notable that the FTC did investigate this issue as part of a merger investigation. But this consent order did not involve any divestiture or behavioral remedy to address any competitive concern with the underlying merger, which is why we were initially divided over whether to classify it as a significant merger investigation. Ultimately, we have leaned towards including it with the data, but it is important to stress that it is not the typical consent agreement. Under the current administration, traditional merger remedies and consent agreements appear to be a nonstarter. To the extent that there have been more abandoned or restructured transactions in recent years, this change in policy may explain that result. Parties who assumed a traditional settlement would be possible short of litigation may have been sorely mistaken.

As explained in our DAMITT Q3 2023 Report, however, 2023 also saw the return of post-complaint settlements after a decade without them. Until this year, the most recent post-complaint merger settlement approved by either U.S. agency involved two complaints filed against Ardagh Group/Saint-Gobain Containers and US Airways/American Airlines in Q3 2013—exactly a decade ago. (Dechert’s Antitrust Group represented US Airways as the buyer on that second deal.) But post-complaint settlements returned in force in 2023, with the agencies collectively settling three separate complaints after the start of litigation. Though seemingly small, that figure is ironically three times the number of pre-complaint settlements. This is a trend worth watching. The most realistic path to an eventual settlement under the current administration may be through litigation. Parties should keep that in mind when considering timing, as discussed below.

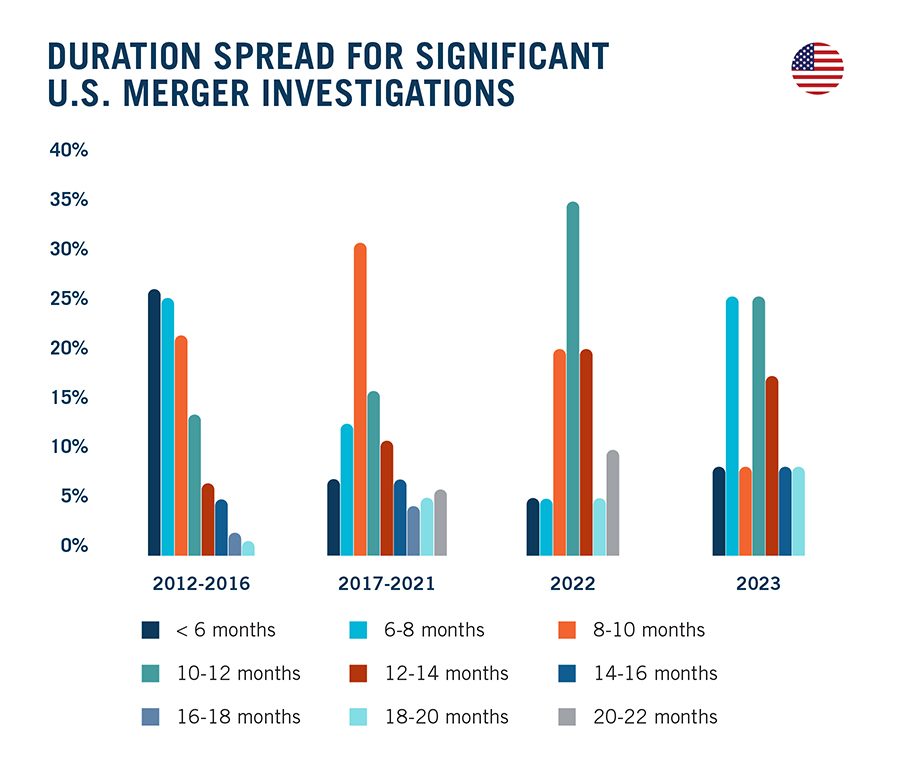

Average Durations Have Declined—But Don’t Hold Your Breath

The publicly-observable average duration of concluded significant merger investigations in 2023 fell to 10.6 months—the lowest since 2018. Similarly, the fourth quarter saw an average duration of 11.2 months, down significantly from the unusual high of 15.0 months in Q3 2023. Before popping champagne corks to celebrate these shorter timelines, however, some words of caution are warranted.

To begin, all but one significant merger investigation in 2023 ended with a complaint or an abandoned transaction. The only investigation resulting in a consent decree lasted 11.5 months and, as described above, even that was not a typical merger settlement.

As a result, the DAMITT average duration for 2023 largely tracks the time to a challenged transaction. Because there were no traditional merger settlements approved, the data do not shed any light on how long it would take to negotiate a traditional merger settlement to a consent decree without litigation. This may help explain why durations have declined in general.

In addition, there appears to have been a divergence over the last year between two different groups of transactions. On one hand, nearly half of the significant merger investigations concluded in 2023 lasted less than 9 months. Only one fifth of significant merger investigations that concluded in 2022 fell under that threshold, so this is a somewhat welcome new trend to watch.

It is unclear what is driving this increase in investigations lasting fewer than 9 months. While these shorter investigations used to be more common, they have become far less common over the last decade or so. It is possible that 2023 may have included more so-called “quick look” investigations or that parties, understanding the increased risk of litigation and reduced odds of a pre-complaint settlement, have become less willing to enter into expanded timing agreements.

Whatever the cause, these shorter investigations were relatively evenly split between the U.S. agencies and between complaints and abandoned transactions. For abandoned transactions in particular, it is possible the parties just did not plan for enough time to get through a full investigation.

Of course, even among shorter investigations, investigations below 6 months—which represented one fourth of transactions between 2012 and 2016—were nearly nonexistent in 2023. The data continue to suggest 6 months is just not enough time to get through a significant merger investigation looking forward.

On the other hand, just over half of the significant merger investigations concluded in 2023 lasted more than ten months. Among these, one-third lasted more than 15 months. These longer investigations were evenly split between complaints and abandoned transactions, but all investigations lasting more than 15 months were abandoned. Most investigations lasting between 10-15 months resulted in a complaint, but keep in mind: parties that receive complaints also need additional time to defend their transactions.

On that score, the time to litigate a merger challenge can vary between 6 and 12 months. As described further in our DAMITT Q3 2023 Report, the average duration for complaints filed in 2022 to a court decision fell to just under 7 months. For complaints filed in 2023, the average duration ticked up to just over 8 months, but that average may be deceptive given a wide disparity between the two matters covered. On the one hand, the FTC challenge of the IQVIA/Propel Media transaction was done in a blazing 5.5 months, whereas, on the other hand, the DOJ challenge of the JetBlue/Spirit merger took more than 10.5 months. Over the last two years, the average duration of FTC litigation has been 6 months, whereas the average duration of DOJ litigation has been nearly 8.5 months. These numbers do not include the three matters that were concluded with post-complaint settlements over the last year. For those matters, the average duration from the complaint to the settlement was 5.9 months.

On a final note, none of these durations take into account proposed changes to the HSR rules that are expected to substantially increase burdens on parties filing notifications and may require additional time to prepare initial HSR filings. Any delays to initial HSR filings under the new rules, once finalized, can be expected to increase durations in the future.

EU Merger Enforcement Remains Stable While Increasing Complexity Leads to Longer Durations and Uncertainties for 2024

Low Numbers of Significant EU Merger Investigations and the Near Extinction of Phase I Remedy Cases Hide the Vigor of EU Merger Enforcement

With 13 significant merger investigations concluded in 2023, the EC beat by a nose its transatlantic counterparts. This is only the second time the EC has finished ahead of the U.S. since DAMITT starting tracking, buttressing the concerns about the health of U.S. merger enforcement noted above.

But is EU merger enforcement really in better health than merger enforcement in the U.S.? Looking at the total number of significant EU merger investigations concluded in 2023, the EC concluded only 13 significant cases—34 percent below its average between 2011 and 2022.

Breaking this down, the EC concluded nine cases following in-depth Phase II investigations, approximately 10 percent more than its 2018-2022 average. By contrast, the number of Phase I Remedy cases dropped to four, a record-low not observed since 2011. This 65 percent dive below average is not compensated by either the 10 percent increase in Phase II investigations or the eight percent decrease in EU merger notifications following the 2023 global M&A activity slowdown. On this basis, an analysis of the EKG of the EU patient shows a lower heart rate that offers some cause for concern.

However, just like any good doctor does not reach a diagnosis based on a single measurement, we have sent the patient for further examination. And the x-ray—allowed by the granularity of information published by the EC—reveals a different picture.

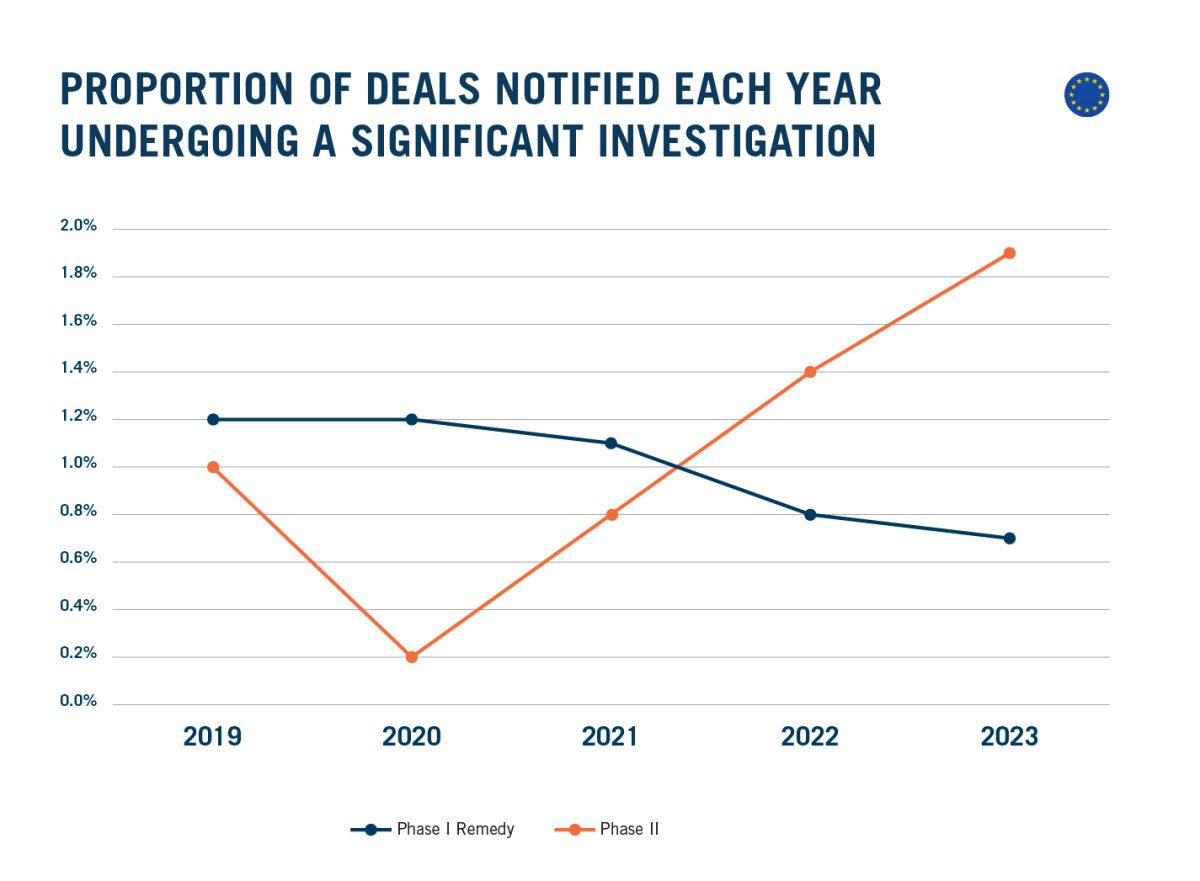

First, the total number of significant EU merger investigations for deals notified in 2023 is expected to reach approximately 18 once pending significant investigations have concluded. This is an 8 percent decrease from the 2017-2022 average, which is on par with the decrease in notifications. Looking at the proportion of notified cases triggering a significant investigation, the EC started a significant investigation in approximately three percent of cases notified in 2023, in line with the average rate since 2019.

Second, breaking down the proportion of filings per month triggering a significant investigation between Phase I with remedies and Phase II cases, the curious case of disappearing Phase I Remedy cases appears less mysterious. The observed drop in Phase I Remedy cases is indeed closely correlated with an increase in the proportion of cases going to Phase II.

This data shows that cases with substantive issues are more likely than ever to undergo a Phase II investigation. This trend towards more in-depth investigations is clearly linked to the need for the EC to get additional time to review the deal (as discussed further below).

Two trends affecting the substantive analysis of merger cases likely explain why the EC has needed more time to investigate in recent years.

First, recent cases have shown the EC’s willingness to explore novel – and more complex – theories of harm. In September 2023, for example, the EC blocked Booking’s bid for flight booking platform eTraveli based on a novel ‘ecosystem’ theory of harm.

The EC considered that the transaction would have enabled Booking to strengthen its dominant position in its core market by expanding the ecosystem of services it offers to customers. As reported in our DAMITT Q3 2023 Report, the EC made it clear that it intends to follow the same approach in the future if warranted by the facts of a case.

Along those lines, the EC may be further encouraged to explore new paths following the recent ruling of the EU Court of Justice in CK Telecoms (Case C-376/20 P). There, the Court found that, to intervene in a merger, the EC only needs to show that the merger is “more likely than not” to result in a significant impediment to effective competition, as opposed to the higher standard previous applied by the General Court, i.e., establishing a strong probability of the existence of a significant impediment to effective competition. The Court ruling is expected to bolster the EC’s position to challenge mergers more assertively, particularly in oligopolistic markets and based on novel theories of harm.

The second trend affecting the substantive analysis in significant merger investigations is the increasing openness of the EC to behavioral remedies. The EC accepted behavioral remedies in 33 percent of significant investigations concluded in 2023, an increase of 21 percentage points from the average between 2018 and 2022. The fact that in each case these commitments were accepted following an in-depth investigation seems to confirm that more time is needed to assess suitability.

Here, merging parties should take some comfort in the fact that the increased scrutiny of deals does not correlate with stronger interventions. After peaking at 33 percent in 2022, the percentage of significant investigations resulting in a blocked or abandoned transaction fell to a more modest 15 percent in 2023. As shown below, there is a stark contrast with the U.S. in this area. The EC is taking more time to investigate transactions, but that time includes the added effort to work through and approve potential commitments rather than rejecting most remedies out of hand like its counterparts across the Atlantic.

The Average Duration of Phase II Investigations Continues to Decline While the Duration of Phase I Remedy Cases Skyrockets

In terms of timing, the average duration of EU Phase II investigations continues to slowly decline. Phase II investigations concluded in 2023 averaged at 17.3 months, a month faster than in 2022 and nearly two months faster than the record-high of 2021.

Breaking this duration down between pre-filing discussions and formal review, 2023 saw the EC revert to pre-2022 trends, with formal review accounting for just shy of half of the total investigation period. This confirms that the record-high 11.2-month duration observed in 2022 was just a temporary adverse effect of Covid 19, driven by unprecedented lengths of suspension of some investigations. Still, the EC used its statutory powers to “stop the clock” in 67 percent of cases in 2023, suspending the review for three months on average. The EC also agreed to “voluntary” extensions with the merging parties in all but two cases.

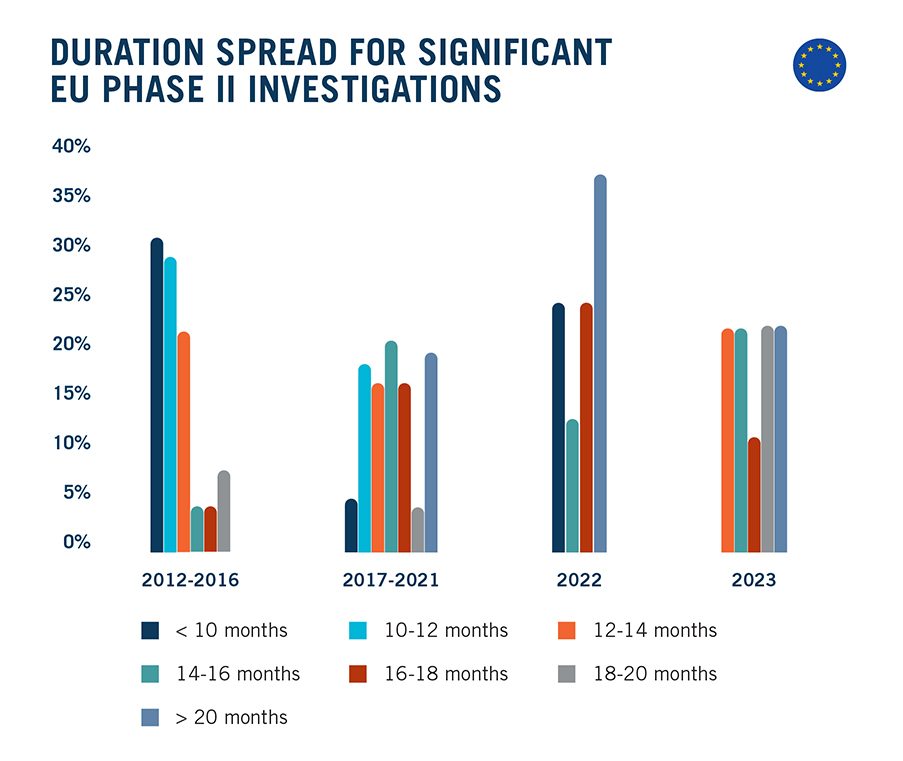

Looking at the duration spread, significant EU Phase II merger investigations concluded in 2023 were evenly spread between 12 and 23 months. The relative increase in “shorter” Phase II investigations in 2023 compared to 2022 may be driven by the influx of cases that would historically have been cleared in Phase I with remedies.

As set out above, we noticed the EC progressively shifting away from agreeing to remedies in Phase I in favor of Phase II investigations. While this trend is likely explained by the need for added time to assess the remedies, it still means that the EC is dealing with cases that could be relatively simpler than traditional Phase II cases. As such, these may have been cleared within a shorter time frame.

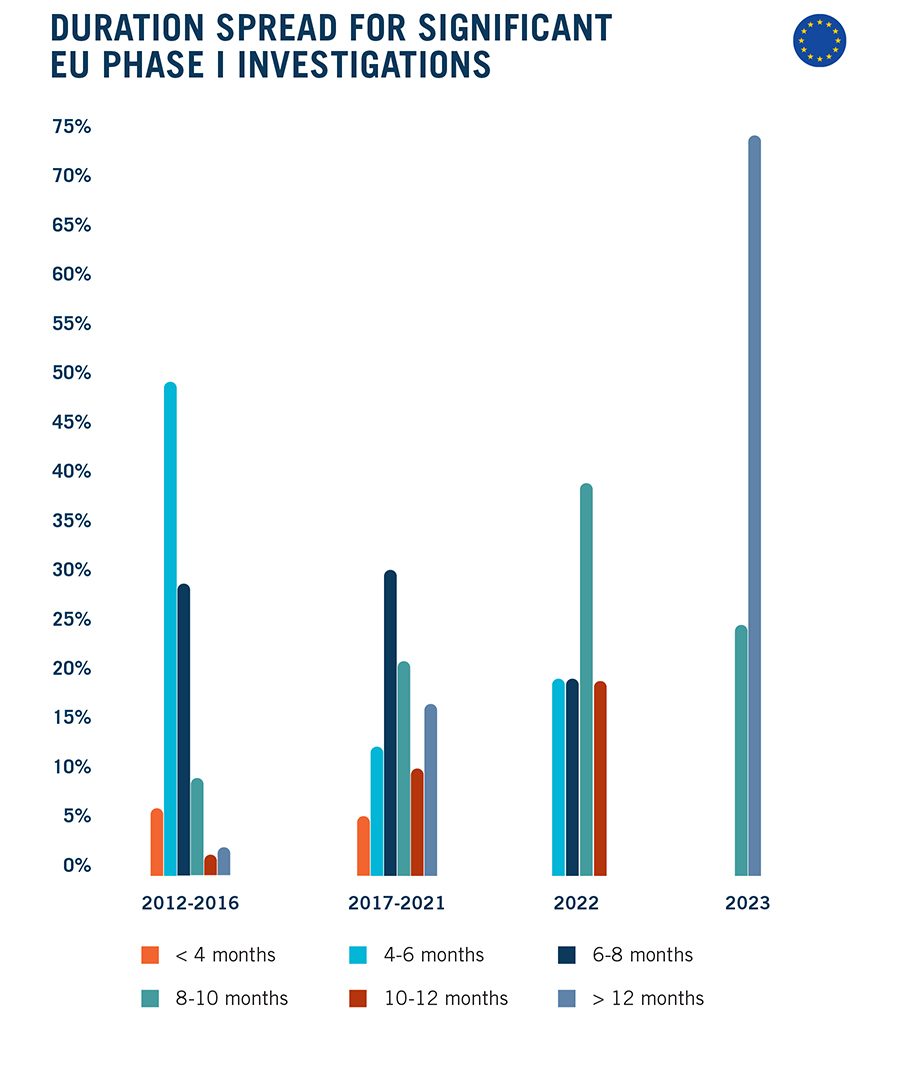

Interestingly, the very limited number of cases that still managed to achieve clearance with remedies in Phase I took significant time to do so, even longer than many Phase II investigations. Average duration of Phase I remedy cases indeed increased to a DAMITT record of 13.1 months in 2023, nearly 50 percent longer than the 2018-2022 average for Phase I Remedy investigations and even higher than the 2011-2016 average for Phase II. Moreover, three of the four investigations lasted more than 12 months, with the average only brought “down” by a single short investigation falling under a year.

These increasing durations are once again driven by the exponentially increasing length of pre-filing discussions, since the formal review period is set by the EU Merger Regulation at a maximum of 35 working days in Phase I.

In 2023, the average duration of pre-filing discussions for EU Phase I Remedy cases reached an all-time high of 11.3 months, longer than any average recorded since DAMITT started tracking, even for Phase II investigations.

It should be noted that these extreme pre-filing durations are also driven by the increased use of pull and refiles—a tool that is common in the U.S. but was seldom used in EU cases in the past. All but one of the cases cleared in Phase I with remedies in 2023 were pulled and refiled, adding on average 19 working days of “formal review” by the EC.

As reported in our DAMITT Q3 2023 Report, this is a marked departure from previous practice in Europe, where pull-and-refile cases were infrequent. In 2023, pulling and refiling Phase I Remedy deals added on average 130 working days to the clock. Only one case was pulled and refiled before a Phase II investigation. If this trend continues, it will provide reasons to question the relevance of the 35-working-day cap of the formal Phase I review period provided by the EUMR, which increasingly exists just in theory.

While these durations may look frightening, merging parties should keep in mind that only a minority of cases are subject to significant merger investigations. Indeed, 80 percent of cases concluded in 2023 were handled under the simplified or super simplified procedure. The simplified procedure has been a constant feature of EU merger control since 2013, and a very successful one. Cases reviewed under the simplified procedure in 2023 lasted 17 working days on average.

The EC partially revised the merger review process in 2023 to better focus its resources on cases raising concerns and reduce the administrative burden of reviewing the ones that do not. To this end, it adopted the Merger Simplification Package in April 2023, allowing for more deals to be reviewed under the simplified procedure and introducing a new “super simplified” procedure. Under the super simplified procedure, parties can submit a filing without pre-notification talks using an updated ‘tick the box’ form which streamlines questions relating to the substantive assessment of the merger. This sharply contrasts with the U.S., where notifications for all filers are expected to become far more complex over the next year.

In total, 18 cases were notified in 2023 under the new super simplified procedure. While the average duration of the formal review of these deals is broadly on par with deals notified under the simplified procedure, i.e., 16.9 working days, the absence of pre-filing discussion allows for a significantly faster process overall.

2024 – A Year to Watch

The trends highlighted above are likely to continue in 2024, but additional factors will make 2024 a fascinating year for merger enforcement in Europe.

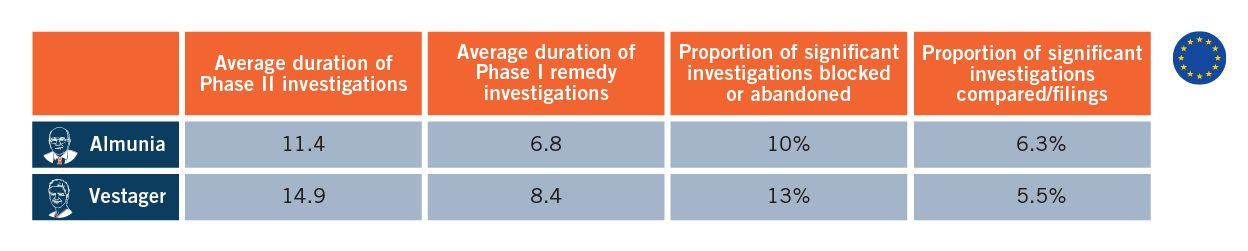

First, EU Commission Executive Vice President (EVP) Vestager returned to the EC at the end of 2023 for what may be her last year or so leading EU competition law enforcement. While she indicated her willingness to stay for a third term, it is unclear whether the Danish government would nominate her or prefer someone closer to the ruling political party. EVP Vestager may want to ensure her legacy over the next six months which could lead to stronger enforcement. Since EVP Vestager has been in office for most of the period tracked by DAMITT, any comparison with her predecessor, Commissioner Joaquin Almunia, would be approximate – due to the rapid changes in merger control processes and fluctuating nature of M&A activity – and should be taken with caution. A high-level review of the data can, however, provide some insights: the Vestager era seems to have led to longer investigations and higher risks of deals being blocked or abandoned, albeit with a lower number of notified cases being subject to a significant merger investigation.

Second, while the new approach to Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation has not (yet) resulted in a significant increase in cases – the EC accepted a referral under the new approach in only three cases so far, with two still in pre-filing discussions – these developments still warrant close monitoring. In particular, the EU Court of Justice is expected to rule in 2023 on the appeal against the decision to accept the referral in Illumina / Grail. If the Court validates the EC approach, it may result in an increase in cases referred on this basis. In terms of outcome, the only concluded investigation following an Article 22 referral under the new approach so far led to a prohibition. 2024 will see more concluded Article 22 investigations, allowing for an assessment of the likelihood of a deal being cleared after a referral under the new approach to Article 22. It will also allow for a comparison in terms of outcome between deals referred under the traditional Article 22 approach, i.e., deals meeting the jurisdictional threshold in at least one Member State, and the new approach, i.e., deals falling below the thresholds in all EU Member States.

Finally, with the Digital Markets Act now in force designated gatekeepers are required to inform the EC of any deal “where the merging entities or the target of concentration provide core platform services or any other services in the digital sector or enable the collection of data.” While this is not a fully-fledged notification obligation, the DMA clearly spells out that Member States can use this information to refer the deal for review under Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation. In line with its commitment to transparency, the EC committed to publish the information received on its website, with a delay of at least four months. At the date of this report, only one transaction has been disclosed and no further steps were taken, but it will be a new area to watch in 2024.

Conclusion

Parties to transactions subject to significant merger investigations continue to face an elevated risk of seeing their deal blocked or abandoned on both sides of the Atlantic, even if the intervention rate shows relatively few deals receive this level of scrutiny. To ensure the ability to defend their deals through a potential investigation, parties to the average “significant” deal in the U.S. should plan on at least 12 months for the agencies to investigate their transaction and may want to add on additional time to address the continuing uncertainty at the agencies. Parties should also plan for another 6 to 12 months if they want to preserve their right to litigate an adverse agency decision.

On the EU side, parties to transactions likely to proceed to Phase II should allow for at least 17 months from announcement to clearance and should not rely on the theoretical deadlines provided for in the EU Merger Regulation, even after a deal has been formally notified. Parties should be aware that the EU Commission is less and less likely to accept remedies without an in-depth investigation; if parties still plan on obtaining a Phase I clearance with commitments, they should factor in around 13 months from announcement to a decision, with significant time set aside for pre-notification talks with the Commission and the potential need to pull and refile their filing.