DAMITT 2025 Review: Merger Investigations Neared Record Lows and Remedy Policies Shifted

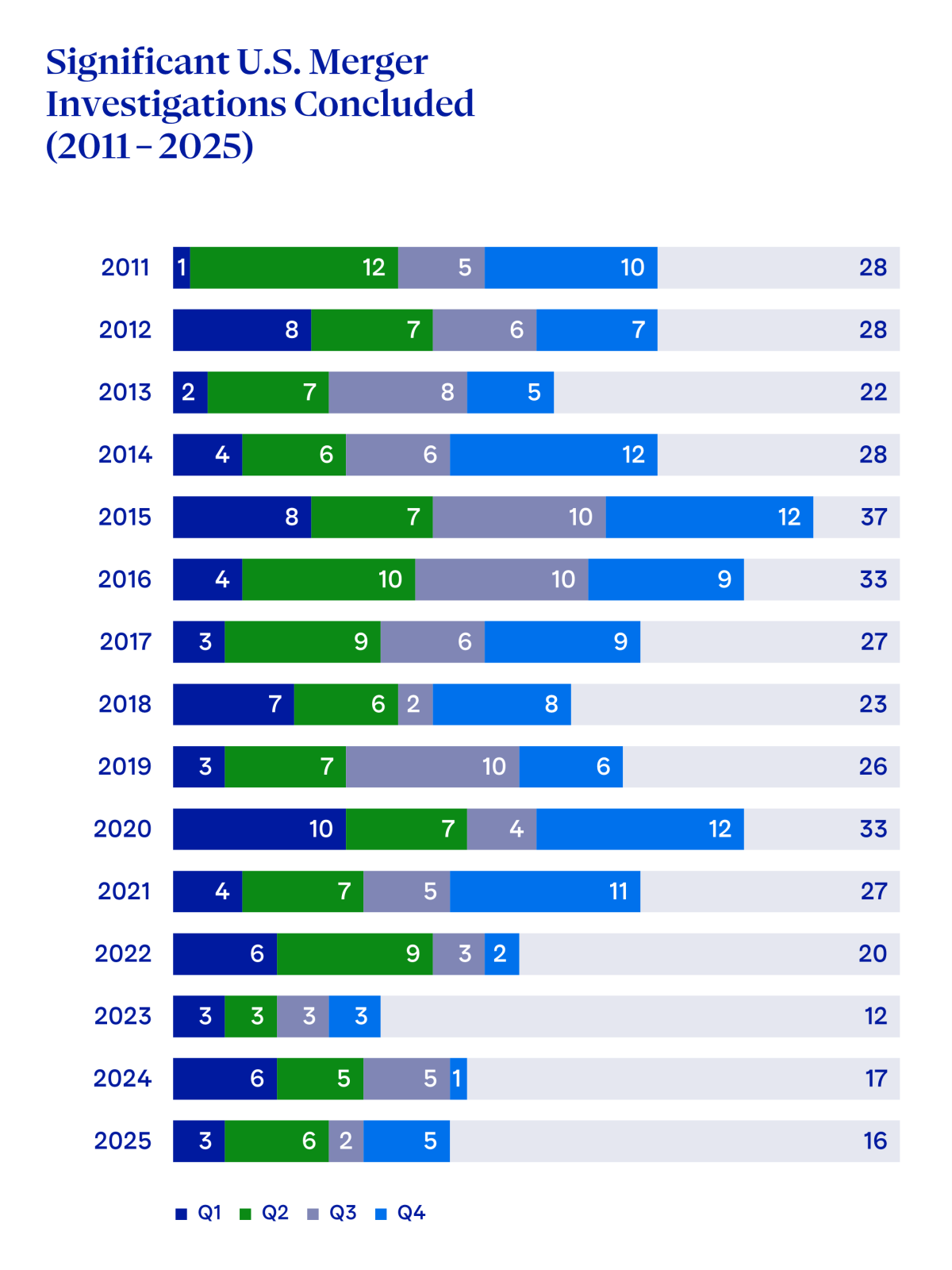

DAMITT, the Dechert Antitrust Merger Investigation Timing Tracker, is the leading source of analysis for significant U.S. and EU antitrust merger investigation and litigation trends. In 2025, both recorded near-record lows, with the second-lowest number of significant merger investigations in DAMITT history.

Key Facts

United States

- Near-record Low Volume: The U.S. agencies concluded 16 significant merger investigations in 2025—the second lowest in DAMITT history and well below the 27 concluded in the first year of President Trump’s first term.

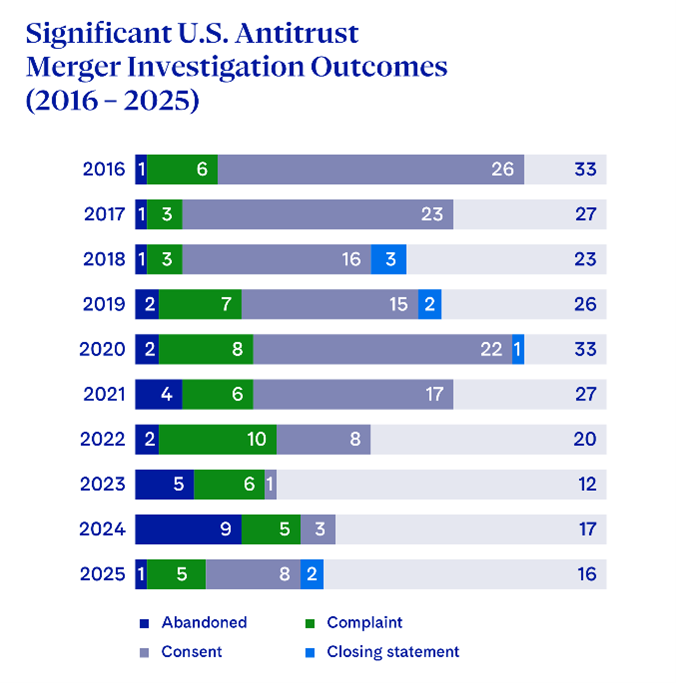

- Merger Settlements Back in Play, While Deal Abandonments Plunge: A total of 8 significant merger investigations concluded with a pre-complaint settlement in 2025, the most since 2022, while abandonments plummeted from a record 9 in 2024 to just 1 in 2025.

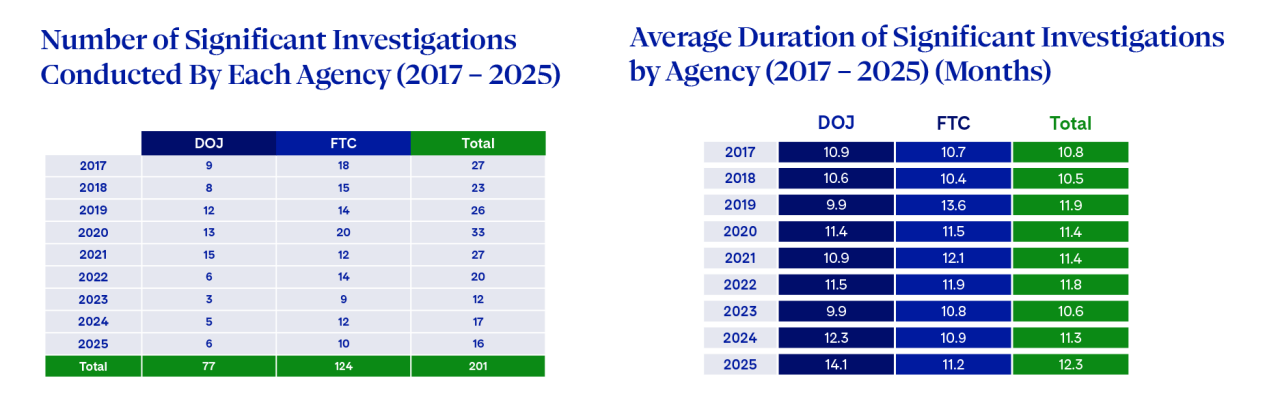

- Record-long Durations: The average duration of a significant U.S. merger investigation from deal announcement to conclusion rose to 12.3 months in 2025, up from 11.3 months in 2024. But there are positive signs on the horizon—deals announced in 2025 averaged 9.3 months, down from 11.3 months for 2024-announced deals, suggesting that average durations of significant investigations are shortening under the current administration as the backlog is cleared.

European Union

- Low Enforcement Persists: Only 11 significant merger investigations were concluded in 2025, which remains very close to 2024, which marked a record-low of 10. The EU enforcement rate stayed very low at 3%, up from 2% in 2024. No significant investigation resulted in a blocked or abandoned transaction in 2025, contrasting with an exceptional 20% rate in 2024.

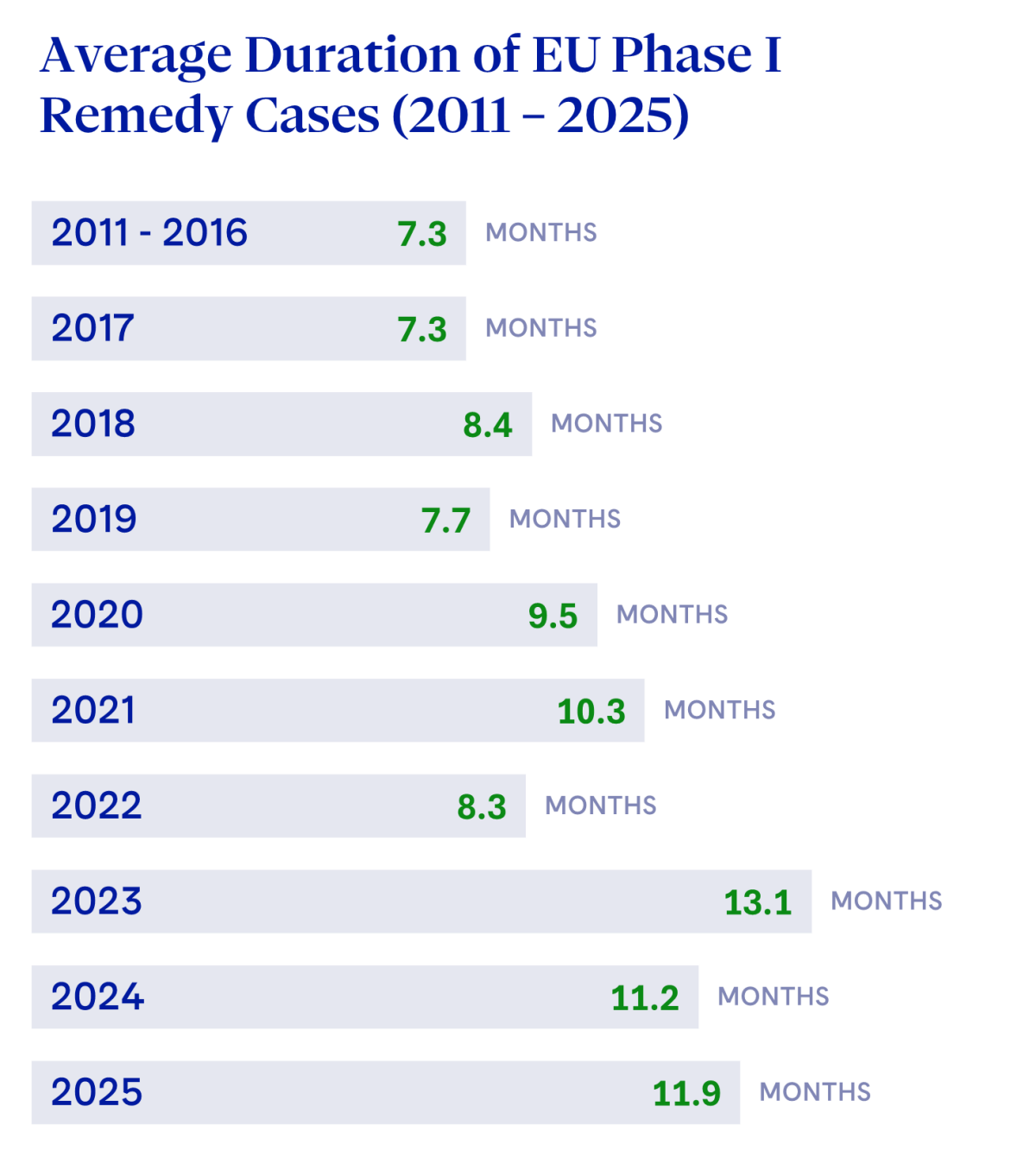

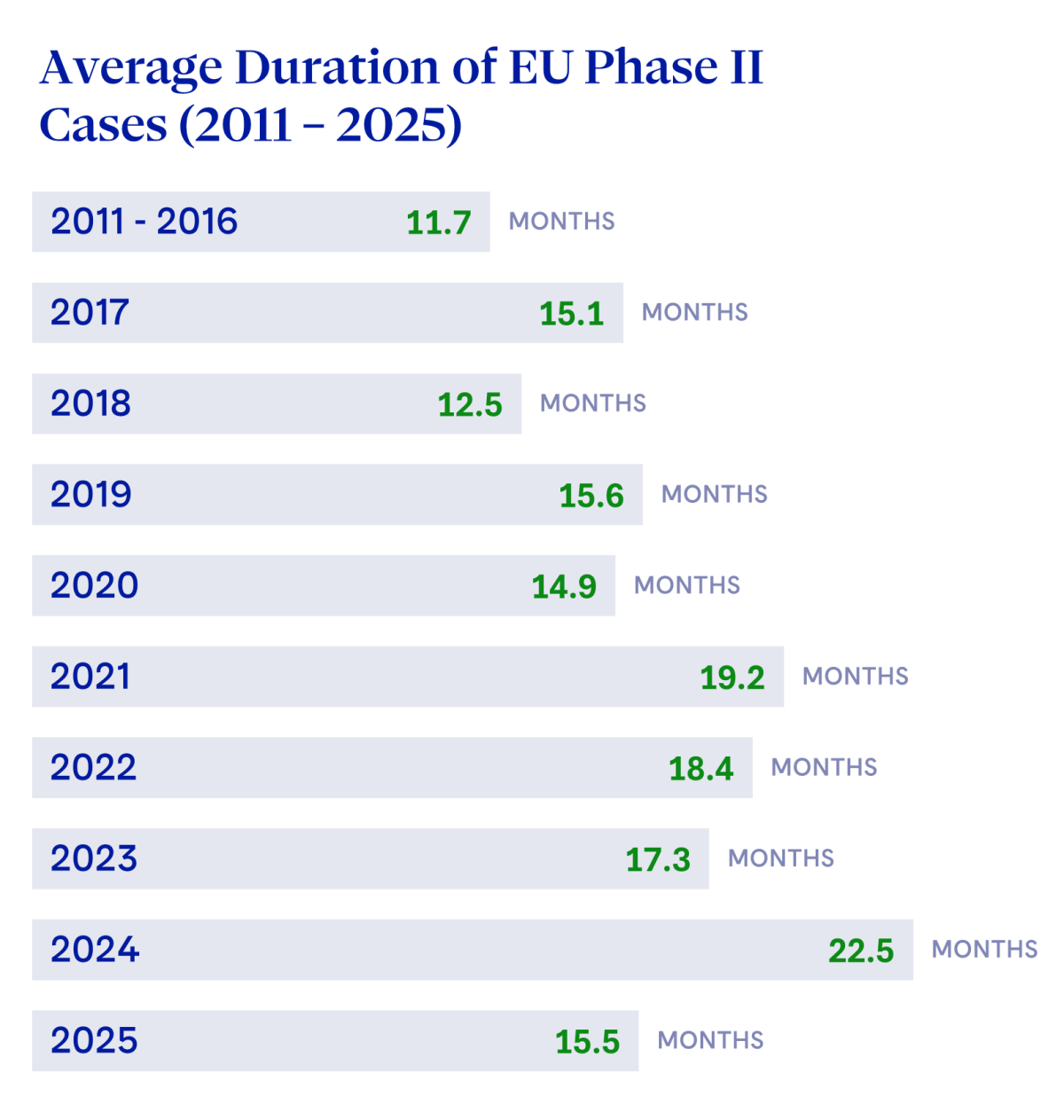

- Phase II Speeds Ahead, Phase I Remedies Still Drag: The average duration of Phase II investigations in 2025 was 15.5 months, down from 22.5 in 2024. This can be partly explained by the fact that only two Phase II mergers were concluded; meanwhile, the average duration of Phase I remedy cases is going up again, now settling at 11.9 months—roughly 6% above 2024 and still 20% above the 2019-2024 average.

- Increase of Fix-it-First and Upfront Buyers in Phase I: The EU Commission is increasingly requiring upfront buyers or fix-it-first remedies in Phase I, which adds to the overall duration of Phase I merger review; Phase II investigations were, by contrast, remarkably low and closed without any remedies.

United States

Reduced Volume of Significant U.S. Merger Investigations Under Biden Carries into Start of Trump’s Second Term

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ) concluded 16 significant merger investigations in 2025, the second lowest in DAMITT’s 15-year history behind only the 12 recorded under the Biden administration in 2023. This near-record low lagged well behind Trump’s first year in 2017 (27), his first-term average (27), and the 2011–2024 DAMITT average (26).

As first reported in the DAMITT Q1 2025 Report, historical voting dynamics at the FTC point to a strong bipartisan enforcement consensus. In 2025, due to the departures and firings of the Democratic Commissioners, only one of the ten FTC significant merger investigations was decided by a Commission with both parties represented—and it was unanimous: a 4-0 vote to challenge GTCR/Surmodics. There were no dissents in 2025, even though DAMITT observed many cases of intra‑party dissents in prior years. Currently, two Republican Commissioners are seated and another Republican nominee (David McNeil) is waiting in the wings, but Trump has not signaled his intention to appoint any Democratic Commissioners.

2025 Merger Enforcement Reset: Pre-Complaint Settlements Surge under Trump While Deal Abandonments Plunge

The trend of significant merger investigation outcomes shifted sharply in 2025. DOJ and the FTC agreed to 8 pre-complaint consents to settle merger probes. As noted in our DAMITT Q2 2025 Report, that’s welcome news for dealmakers as it allows companies to negotiate divestiture commitments in transaction agreements to reduce the risk of a deal breaking and increase the odds of closing. Settlements also enable the agencies to achieve merger enforcement victories without expending substantial resources on litigation while taking on the risk of losing at trial.

At the same time, abandonments collapsed in 2025. The agencies logged their first and only abandonment of 2025 in December (Aya Healthcare/Cross Country Healthcare), falling well short of the record high of 9 abandonments in 2024. With pre-complaint merger settlements back as a realistic option for merging parties, fewer abandonments are unsurprising. For historical context, during Trump’s first term, the agencies took credit for just 6 abandonments but 76 consents, compared to 20 abandonments and just 29 consents (with 17 in the first year) during Biden’s term.

The U.S. agencies filed 5 complaints in 2025, but only 4 were initiated under Trump. DOJ’s AmexGBT/CWT challenge, filed in the waning days of Biden’s term, was eventually dismissed under Trump—the first unconditional withdrawal of a merger challenge in DAMITT history as previously reported. Of the 4 Trump-initiated complaints, 1 settled post-complaint (HPE/Juniper) and awaits court approval amid state interventions in the Tunney Act proceedings; 2 went to trial, as discussed below; and the most recent was filed in December and remains pending.

Finally, the U.S. agencies revived closing statements, issuing 2 in 2025 after the Biden administration issued none. Closing statements can reveal the agencies’ merger-enforcement playbook, unlocking insights into how they define markets and analyze competitive effects.

Average Duration of U.S. Significant Merger Investigations Increases to All-Time High, But Trend for Recent Deals Shows Signs of Improvement

The speed of significant U.S. merger investigations remains a sore spot. Average duration rose to an all-time high of 12.3 months in 2025, up a full month from both last year’s near-record high of 11.3 months and the four-year average of 11.2 months during Trump’s first term.

Prior promises of faster merger reviews have not yet translated into shorter timelines in the DAMITT data. Assistant Attorney General Gail Slater closed the year with a “Trust Talk” touting efforts to “restore speed and efficiency to merger reviews,” pointing to the return of early terminations—which were halted at the outset of the Biden administration. Despite the record high average duration in 2025, most of the significant merger investigations concluded in 2025 began under the Biden administration, including Safran/RTX Corporation, which ran over 23 months until DOJ agreed to a settlement under the Trump administration. While the length of that investigation is an outlier, the median duration of significant merger investigations also increased to 11.6 months in 2025—up from 9.1 months in 2017 (Trump’s first year of his first term) and 11.0 months in 2024.

But there are signs of improvement on the horizon. For deals announced in 2025 and reviewed entirely under Trump-era leadership, the average significant investigation lasted only 9.3 months. With only three matters in that set, however, the sample is too thin to determine whether this trend is durable. The new HSR rules may lead to further increases in durations of significant merger investigations. Dechert’s DAMITT team will be watching closely in the quarters ahead to assess the impact of these changes.

FTC Leads DOJ on Number of Significant Merger Investigations—and Finishes Faster in 2025

DAMITT has identified differences and similarities in DOJ and FTC enforcement trends over time. Since Trump’s first term, the FTC has concluded more significant merger investigations than DOJ every year except 2021. The FTC outpaced DOJ again in 2025, completing 10 significant merger investigations compared to DOJ’s 6—and did so faster. The FTC’s average duration was 11.2 months, nearly three months quicker than DOJ’s 14.1-month average. That gap stands out given long-run parity between the agencies—11.3 months on average for DOJ and 11.5 months on average for the FTC going back to 2017.

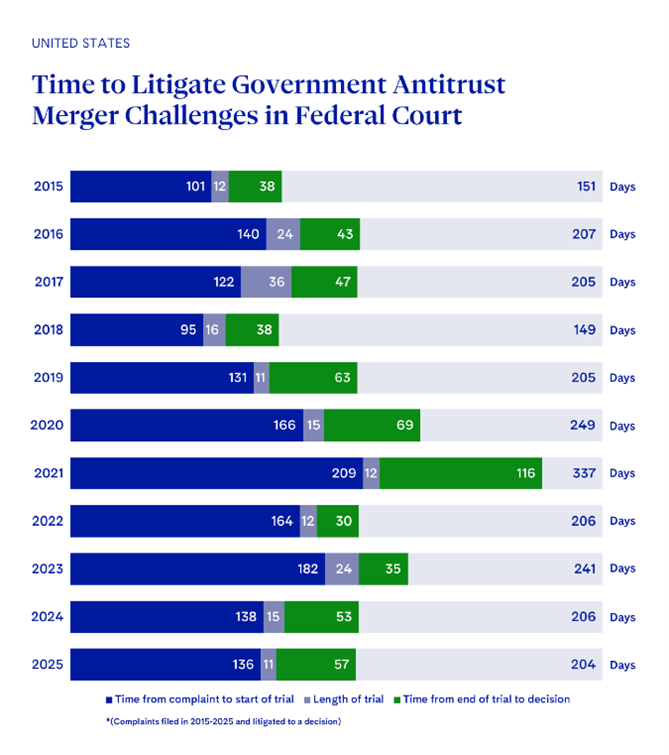

Two FTC-Led Merger Litigations, Two Different Outcomes, and Average Duration of U.S. Merger Litigation Holds Steady

The FTC led both merger litigations filed in 2025 that reached a court decision—losing GTCR/Surmodics and winning Edwards Lifesciences/JenaValve. These merger litigations ran on average 204 days (6.8 months), nearly matching 2024’s average of 206 days (6.9 months) and falling just below the 10-year average of 216 days (7.2 months) across 2015-2024. There was a meaningful disparity in length between these two FTC merger litigations—GTCR/Surmodics ran 250 days (8.3 months) whereas Edwards Lifesciences/JenaValve ran just 157 days (5.2 months). Meanwhile, DOJ steered clear of trial in 2025, settling HPE/Juniper (filed at the outset of Trump’s second term) and UnitedHealth/Amedisys and dismissing AmexGBT/CWT, both of which were filed in last months of President Biden’s term.

In its December 11, 2025 suit to challenge Henkel/A-Paint, the FTC broke with tradition—seeking a permanent injunction from a federal court instead of its usual preliminary relief. Historically, the FTC has argued that a preliminary injunction by a federal court is warranted if the evidence raises questions “so serious, substantial, difficult and doubtful as to make them fair ground for thorough investigation, study, deliberation and determination by the FTC [in administrative hearings] in the first instance and ultimately by the Court of Appeals.” DOJ, on the other hand, routinely pursues permanent injunctive relief and must prove a Clayton Act violation on the full merits of the case without an in-house process in place. Going back to 2015, FTC merger cases have moved from complaint to trial in 131 days (4.4 months) versus the DOJ’s 168 days (5.6 months), and to a court decision in 190 days (6.3 months) for the FTC versus 251 days (8.4 months) for DOJ. If permanent‐injunction requests become the FTC’s new standard, its merger challenges could stretch out to match DOJ’s longer average timelines—including longer pre-trial discovery periods and extended waits for courts to issue final decisions.

European Union

Significant EU Merger Investigations: Limited Number of Major Probes

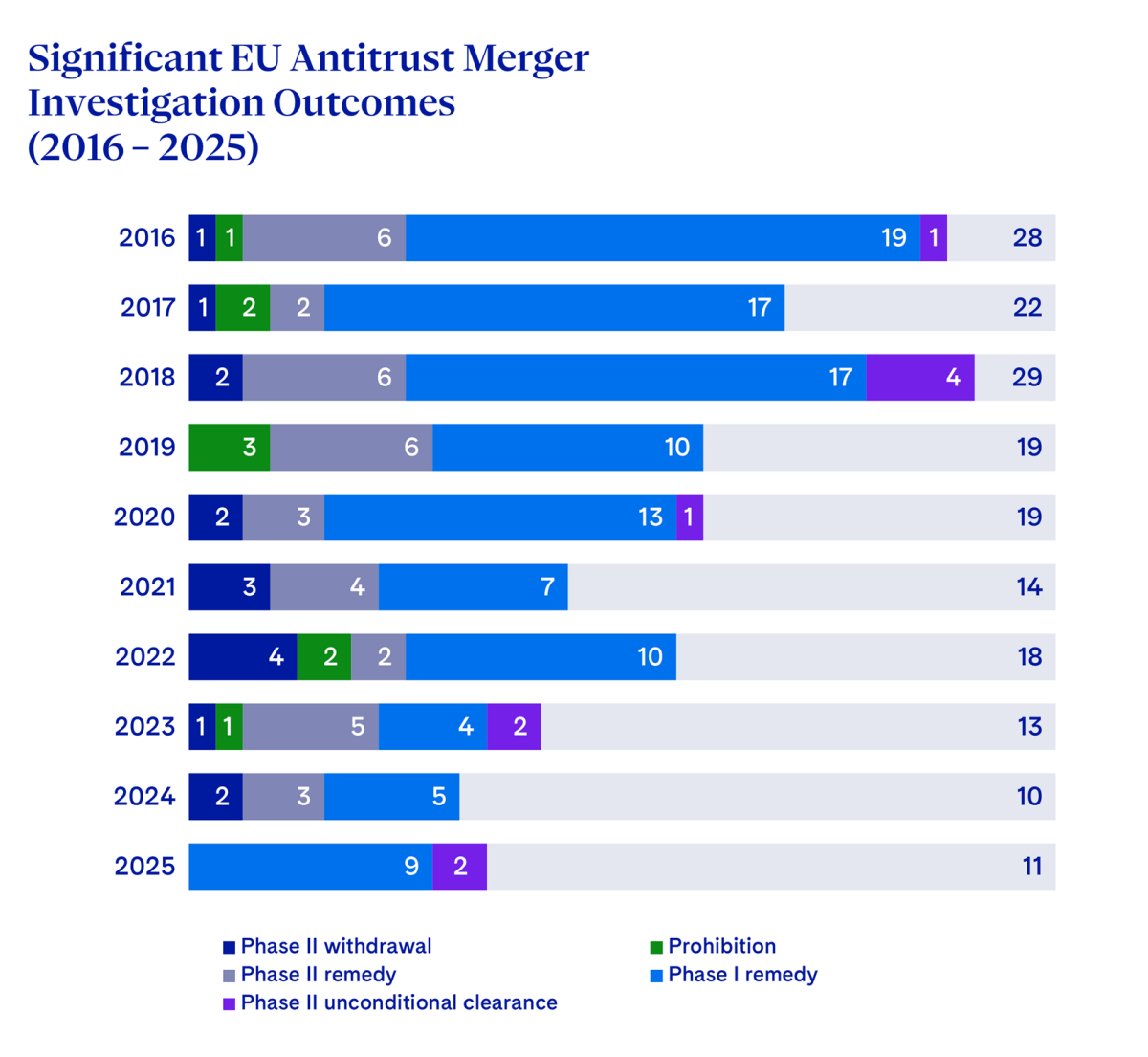

The EU Commission ended 2025 having concluded only 11 significant EU merger investigations, which is roughly in line with 2024’s record-low of 10 over the past 15 years. This small number of significant investigations confirms the downward trend observed over the past few years: the average number of significant investigations fell from 23 in 2016-2020 to 13 in 2021-2025, which represents a decline of over 40%.

But what truly stands out this year isn’t the confirmation of low enforcement activity, but an unprecedented shift toward Phase I remedies and away from Phase II investigations. In 2025, the Commission closed 9 Phase I cases with remedies, with an increasing number of upfront buyers or fix-it-first remedies, while only 2 cases went to Phase II— both were unconditionally cleared which is a rather uncommon outcome. This trend illustrates the EU Commission’s strong preference for swift resolution of competition issues in Phase I rather than pushing cases to Phase II, where there is a higher risk of subsequent litigation before the courts.

In total, there were 384 filings in 2025, showing an overall high level of activity, which nonetheless remains below 2024’s 401 figure.

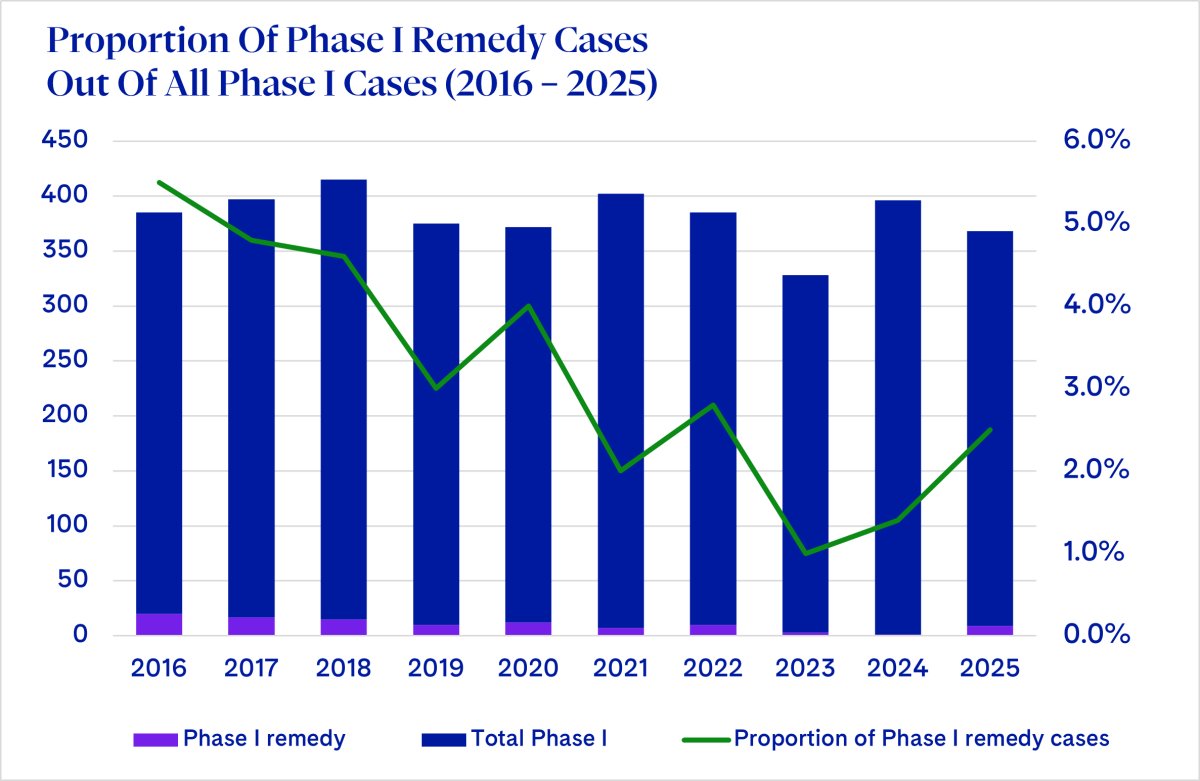

The 11 significant investigations concluded in 2025 put the EU Commission’s intervention rate at a very low 3%; up from 2% in 2024, yet still well below the roughly 6% average since 2011

Phase I Remedies are Back – and on the Rise

Phase I remedies staged a comeback in 2025. Nine of the 359 Phase I decisions included remedies, accounting for 2.5% of all Phase I outcomes, up from 1.3% in 2023-2024, and above the 2020-2024 average of 2.3%. By contrast, Phase II investigations took the opposite direction: in 2025 only 2 significant mergers concluded in Phase II, with both cases cleared unconditionally—a sharp break from 2024, when 5 Phase II investigations resulted in 3 remedy cases.

This pattern suggests matters that might once have gone to Phase II are increasingly being resolved through Phase I remedies, with an uptick in upfront buyers or fix-it-first remedies. What looks like procedural efficiency—the “workhorse of EU merger enforcement,” as the DAMITT Q2 2025 Report puts it—has come with a trade-off: since 2017, Phase I remedy cases have taken longer on average, thus diminishing the time savings parties might expect.

Catching “Killer” Acquisitions: Expansion of Call-In Powers and Revival of Classic Antitrust Tools to Review Below-the-Threshold Mergers

Seeking to plug what it viewed as an “enforcement gap,” the Commission tried to exercise jurisdiction over below-thresholds transactions relying since 2021 on the referral mechanism set forth in Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation (“EUMR”). Since the announcement of this new policy in late 2020, 4 cases were referred to the Commission on the basis of Article 22, leading to:

- One prohibition – later overturned following the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”) ruling of September 2024 in Illumina v. Commission, setting aside the EU Commission’s interpretation of Article 22;

- Two abandonments – though Qualcomm’s acquisition of Autotalks, initially dropped, ultimately closed in June 2025;

- One referral – Microsoft’s acquisition of Inflection, withdrawn following the ECJ’s ruling.

As a result of the ECJ’s ruling prohibiting the use of Article 22 to review transactions falling below EU and Member State thresholds, the burden is now on Member States to catch potentially problematic transactions that would normally escape merger control. And the direction of travel is clear: several of them started making use of or introduced call-in powers in their national merger control regimes, and more are set to follow.

Italy was quick to test the model. Fresh of Illumina v. Commission, it almost immediately used its call-in power to refer Nvidia’s proposed acquisition of Run:ai to the Commission, which accepted the referral in October 2024 and cleared the transaction unconditionally in December 2024 after a simple Phase I review. However, Nvidia has appealed, challenging the Commission’s initial move to accept the referral from Italy. The case is still pending. Whether EU Courts will validate the EU Commission's intervention on the basis of Article 22 following a national call-in remains open to question, with little—if any—movement since last year’s report.

As of today, 12 European States have call-in powers, with others—including France, Belgium and the Netherlands—considering adding the mechanism to their toolkit. By contrast, in jurisdictions like Spain and Portugal, call-in regimes have not been considered for the time being. Those jurisdictions rely instead on market share thresholds which can, in certain circumstances, be an effective way to capture “killer acquisitions” regardless of the parties’ turnover.

Beyond call-in powers, Member States are dusting off “classic” antitrust tools to review below-the-threshold mergers, i.e., Article 102 TFEU (applicable to abuse of dominance) and Article 101 TFEU (applicable to anticompetitive agreements). While Towercast confirmed that ex post scrutiny of mergers under Article 102 TFEU is possible, this is not the case for Article 101 TFEU; but national competition authorities are pushing the envelope. France has led the charge, by invoking Article 102 in the recent Doctolib case and deploying Article 101 in an earlier meat-cutting case. The Netherlands have repealed a statutory provision that previously prohibited the application of national abuse-of-dominance rules to acquisitions, and the Belgian and Dutch competition authorities also initiated investigations under abuse-of-dominance rules—not to mention the Finnish competition authority, which has disclosed having opened ex officio investigations based on such rules.

Phase I Remedy Cases Continue to Take Long, Duration of Phase II Cases Decreases

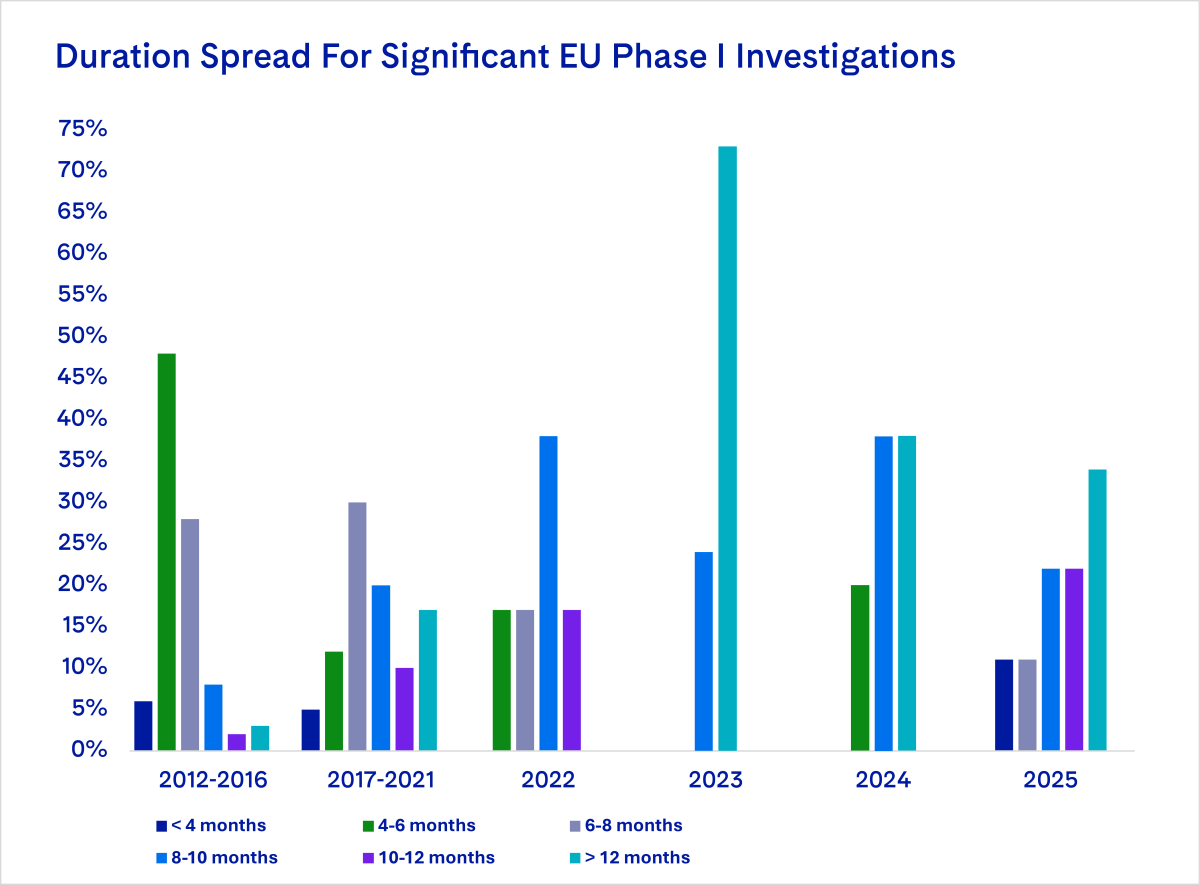

The duration of Phase I remedy investigations increased again in 2025, averaging 11.9 months—up from 11.2 months in 2024 and still about 20% longer than in 2019-2024. The persistence of these timelines points to a “new normal” of longer Phase I remedy cases.

The duration spread does little to assuage concerns: all but 2 cases took more than 8 months from announcement to clearance. Lengthy Phase I reviews continue to be driven by increased pre-notification discussions: despite the 35 working day statutory cap for Phase I remedy cases, parties spent an average of 10 months in pre-notification in 2025.

There was just one pull-and-refile in 2025, which seems to indicate the spike seen in 2023 was a blip, not a trend.

While these durations may look daunting, merging parties should keep in mind that only a minority of cases face significant merger investigations. In 2025—as in 2024—nearly 90% of concluded cases went through the simplified or super-simplified route, which continues to dominate EU merger control and offers far more predictable timelines.

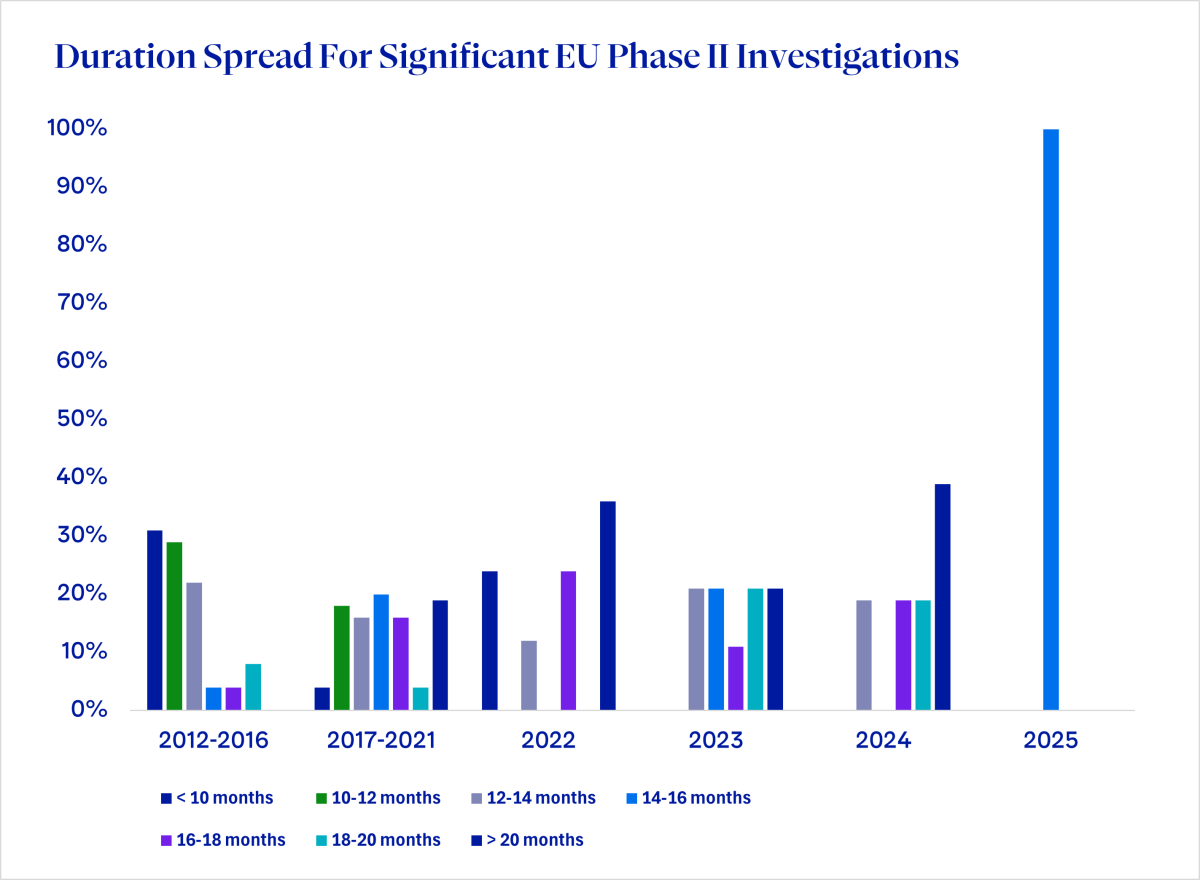

By contrast, the duration of Phase II merger reviews decreased, averaging just 15.5 months—the fastest since 2021 and well below 2024’s 22.5 months (18.2 months excluding the outlier Korean Air/Asiana Airlines case, which dragged on for 39.5 months). This short review duration is explained by the fact that, for the first time since DAMITT began tracking in 2011, none of the cases ended with commitments meaning that there was no need for negotiations with the Commission that typically extend timelines.

In both cases, timing was almost cut in half. While pre-notification discussions averaged 8.4 months, reflecting heavy front-end engagement between the parties and the Commission, the formal review tracked 2024 patterns, averaging 7.1 months.

However, the Commission used its power to “stop the clock” in both Phase II investigations and to agree to “voluntary” extensions with the merging parties in one, underscoring—as stated in last year’s report—its extensive use of these statutory powers to stretch the review period.

Since this sample is small, trends are hard to pin down. That said, both cases concluded between 14-16 months from announcement to decision, which sits in the mid‑range for Phase II reviews.

Review of EU Merger Guidelines

The Commission has launched what it calls a “once in a generation” overhaul of its merger control framework with the review of its horizontal and non-horizontal merger guidelines (the “Merger Guidelines”). The aim is to ensure that the new Merger Guidelines onboard the significant developments and changes seen in merger control over the past 10 years, marked by digitalization and globalization of the economy. The revised guidelines are also intended to better reflect the competitive dynamics of today’s economic environment, particularly with respect to technology-driven markets and ecosystems, innovation and potential competition, as well as sustainability and resilience concerns, as highlighted in the Draghi Report.

From May to September 2025, the EU Commission ran a public consultation on the review of the Merger Guidelines and published the results and a summary of the main points in October 2025 on its “Have Your Say” portal and on DG Competition’s website. The consultation sought input on 7 core themes: (i) competitiveness and resilience; (ii) assessment of market power; (iii) innovation; (iv) sustainability; (v) digitalization; (vi) efficiencies; and (vii) security and labor market considerations.

In addition, the Commission organized 2 interactive technical stakeholder workshops (in December 2025 and January 2026) and will hold a conference in March 2026 to discuss key aspects of the review.

In parallel, the Commission commissioned an economic study on the dynamic effects of mergers, which will also inform the review of the Merger Guidelines. The study aims to provide analytical foundations to assess whether a merger has positive or negative effects on these dynamic factors, and to analyze their relationship with static factors such as price or output changes.

Based on the input collected, the Commission intends to refine its analytical toolkit for merger scrutiny, clarify evidentiary standards for efficiency and innovation claims, and set clearer parameters for remedies that support pro-innovation or pro-investment outcomes. In this context, the Commission has signaled that it may evolve its merger analysis away from static, market-share-based assessments toward a framework that also incorporates dynamic competitive forces, foreseeable market developments and innovation potential.

At a later stage, stakeholders will have the opportunity to comment on a draft of the revised Merger Guidelines which the EU Commission will publish for comments. The feedback will feed into the ongoing review of the EU Merger Guidelines.

Adoption of the revised Merger Guidelines is planned for Q4 2027.

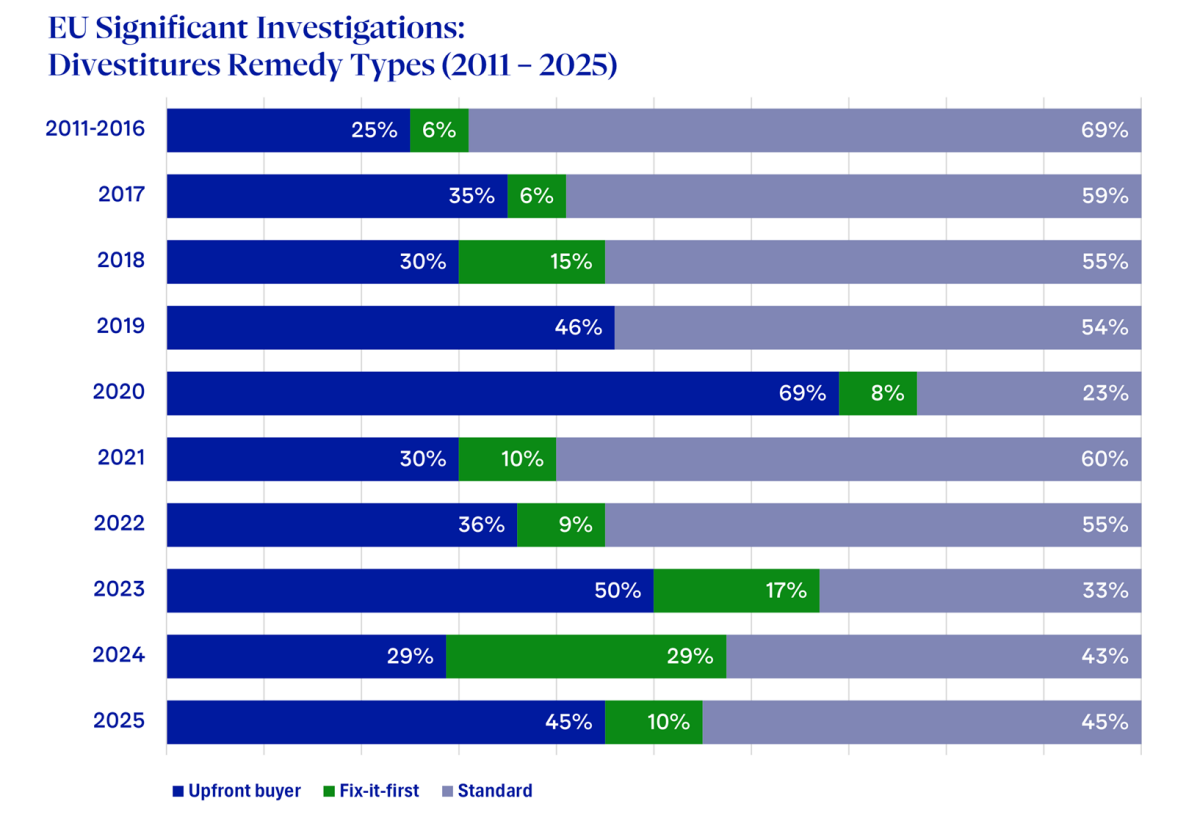

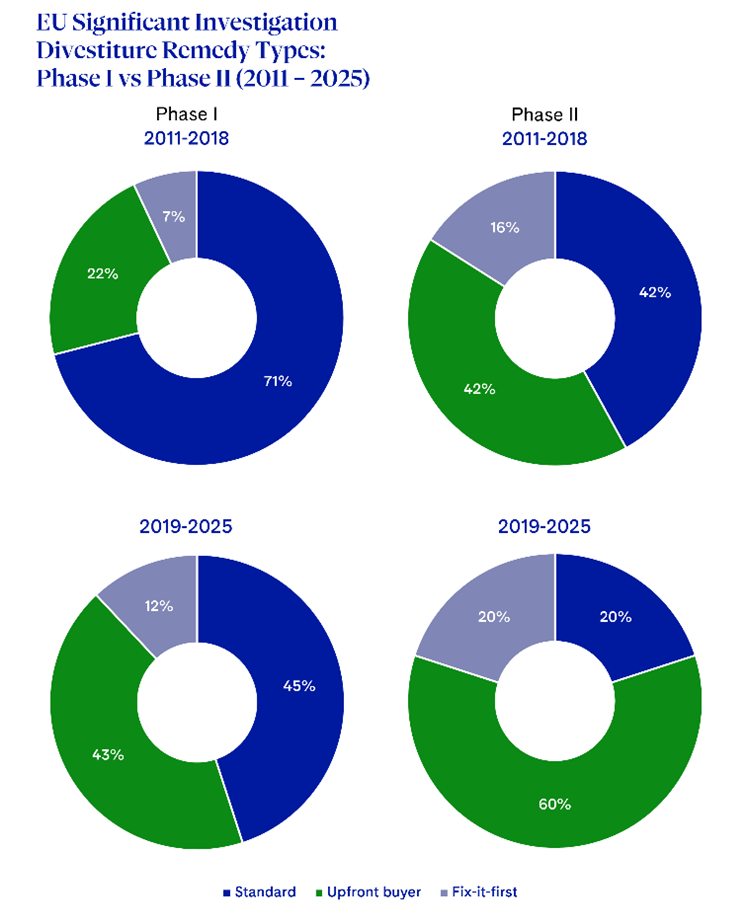

Fix-it-First or Don’t Close: Are Upfront Remedies the New Price to Pay for Phase I Clearance?

In “standard” cases cleared conditionally with structural remedies, merging parties can close their transaction as of the Commission’s clearance decision and then benefit from a specified period (typically around six months) to complete a divestiture to an approved buyer. However, the EU Commission may decide to require a pre-approved divestiture buyer. In the EU, this can either be by way of a “fix-it-first” remedy, which is the equivalent of the “upfront buyer” remedy in the U.S, i.e., requiring the merging parties to obtain approval for a divestiture buyer within the timetable for review of the original notification before the EU Commission will clear the merger. Or it can be by way of an “upfront buyer” EU remedy, according to which the EU Commission will grant conditional clearance at the end of the investigation for a merger without identifying a divestiture buyer—but the companies cannot close the deal until a buyer has been presented to the Commission and approved.

This year marks a decisive shift in Phase I remedy cases, with the share of conditional structural remedies jumping from 29% in 2011-2018 to 55% in 2019-2025.

2025 has seen an uptick in the Commission’s request for upfront buyers or, more exceptionally, fix-it-first remedies. Publicly available data (published decisions or press releases including this information) show that in 2025, 55% of structural-remedy cases included either an EU “fix-it first” or “upfront buyer” requirement—showing that the Commission is increasingly unwilling to allow deals to close before a buyer is found.

Beyond adding a level of complexity for merging parties, these requirements also further delay closing. Looking at Phase I cases that included an “upfront buyer” requirement over the 2019-2025 period, the purchaser was approved on average 5.3 months after clearance. In Phase II cases, the purchaser was approved on average 8 months after clearance.

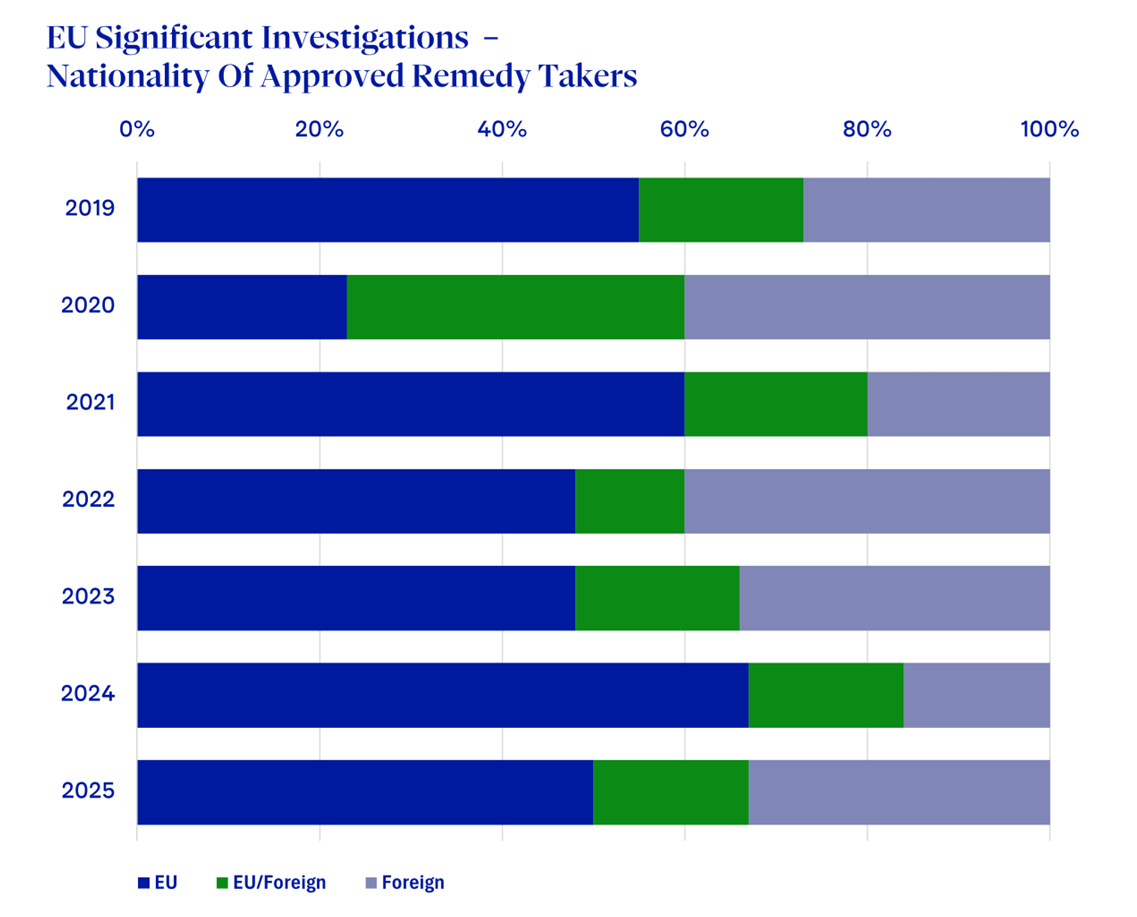

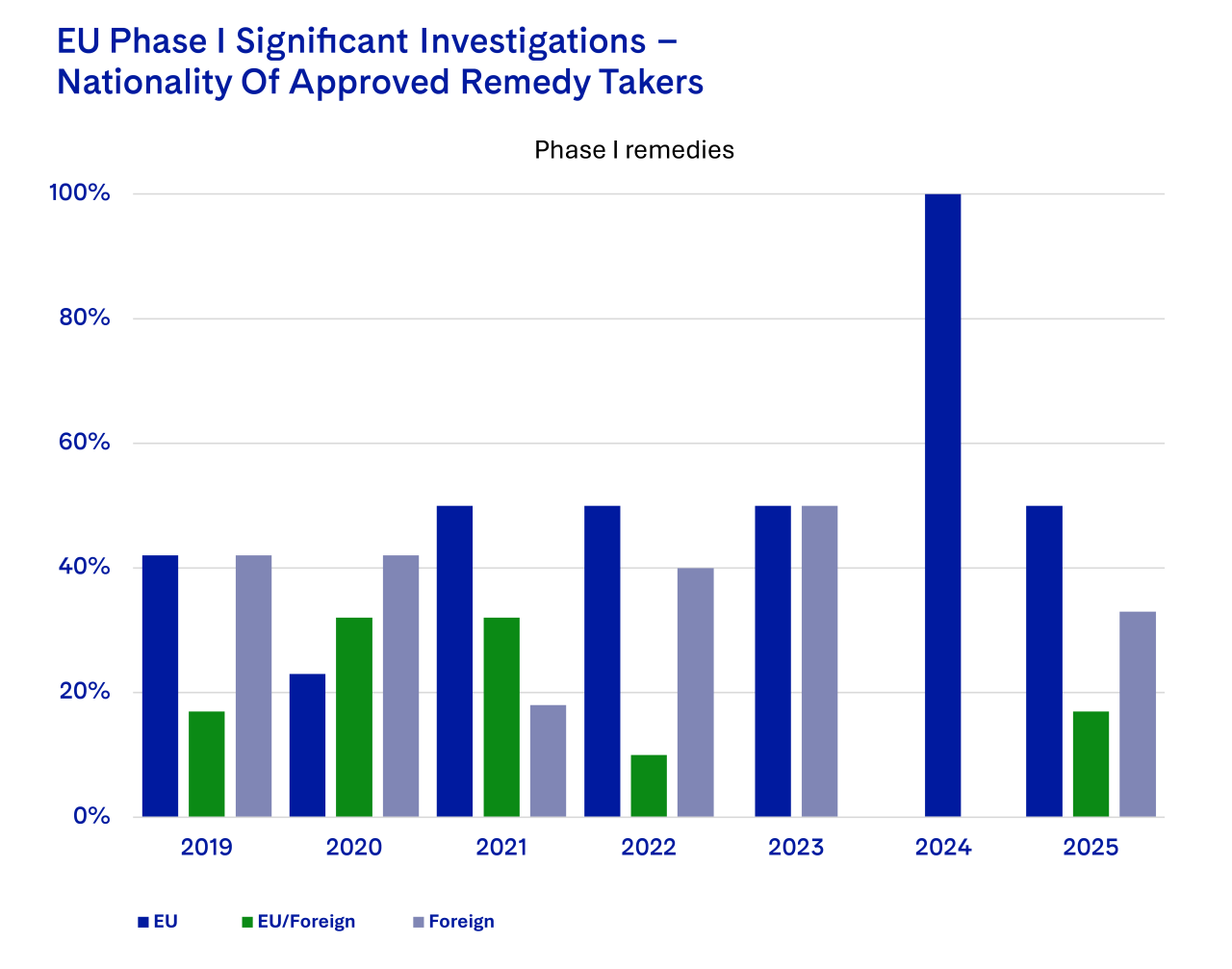

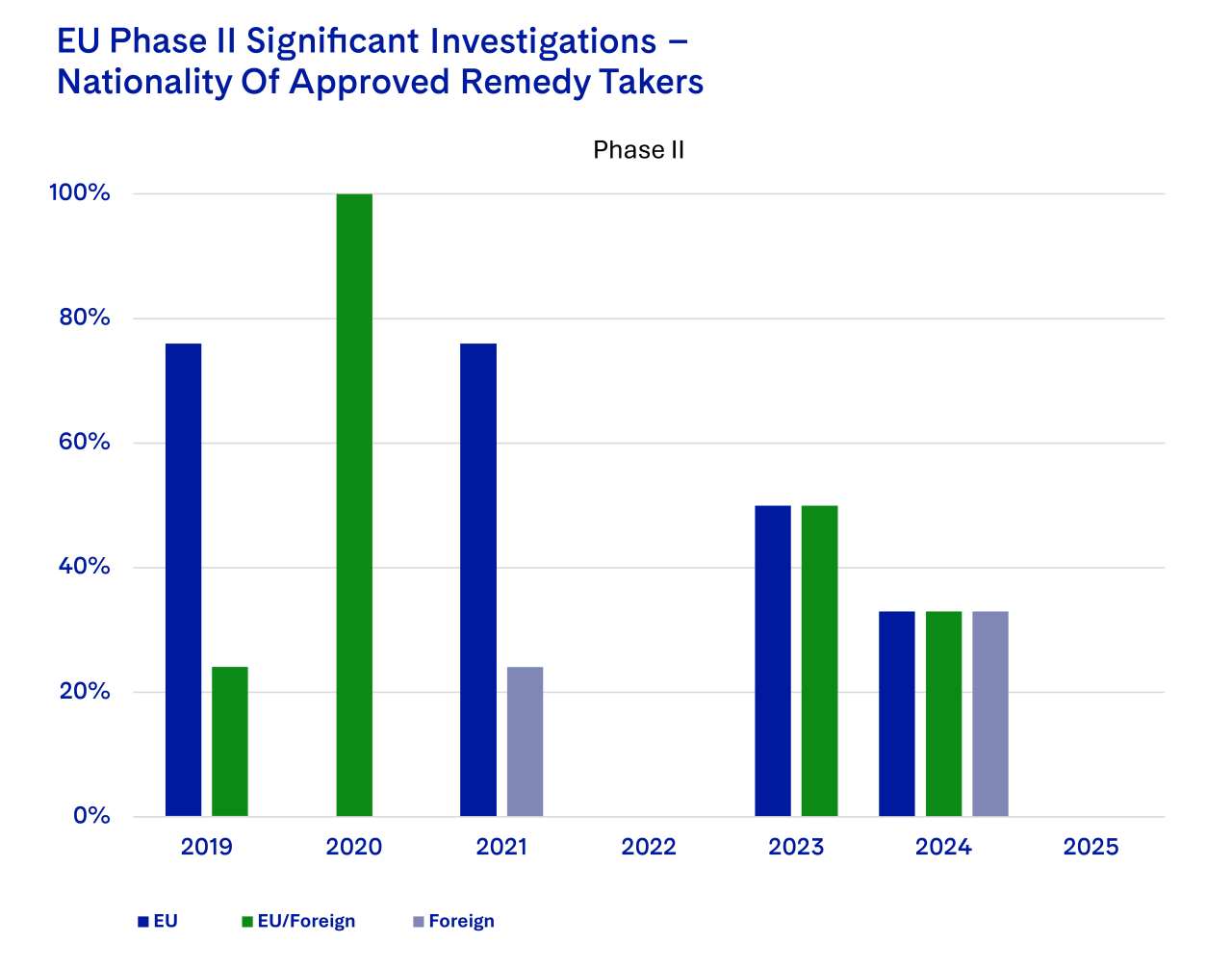

No EU-Only Rule: Commission Approves Foreign Remedy Takers

In 2025, only half of approved purchasers were EU companies (against 67% in 2024), while the percentage of remedy packages including both EU and foreign companies remained the same with 17%. In a third of the cases, remedy packages involved foreign companies only.

As indicated in our previous report, nationality of the purchaser is of course not a formal criterion for approval, and there are many factors that come into play, especially in specific industry sectors.

We will continue to monitor whether the Commission assesses non-EU purchasers in the same way as EU purchasers and whether preferences differ depending on whether a case receives Phase I or Phase II clearance.

Conclusion

United States

Parties to transactions subject to significant merger investigations continue to face an elevated risk of seeing their deals blocked or abandoned on both sides of the Atlantic. To ensure the ability to defend their deals through a potential investigation, parties to the average “significant” deal in the U.S. should plan on up to 12 months for the agencies to investigate their transaction. Parties should also consider allocating an additional 6-12 months in their transaction agreements if they want to preserve their right to litigate an adverse agency decision, for a total of 18-24 months.

European Union

In the EU, parties to transactions likely to proceed to Phase II should allow for at least 15 months from announcement to clearance and should not rely on the EUMR’s formal deadlines, even after formal notification. In the case of below-thresholds mergers that may raise competition concerns, parties should factor in the risk of a call-in followed by a potential referral to the EU Commission, which may add to the overall timeline for clearance. Parties should also be aware that the Commission is increasingly demanding upfront buyers and fix-it-first remedies in Phase I, with a non-negligible impact on closing of the transaction which might end up being significantly delayed. Overall, parties should plan for roughly 12 months to obtain Phase I conditional clearance, from announcement to a decision, with significant time allotted to pre-notification discussions with the Commission.

The authors would like to thank Quentin Colombier for their contributions to this report.